Body of evidence: a fresh look at Freud and Bacon's early careers

By Simon Wilson

Published on 12 April 2018

The two figurative artists are at the centre of Tate Britain's 'All Too Human' exhibition, but they haven't always been so favoured. Here we look back to a time when a young Bacon and Freud were much ignored.

From the Spring 2018 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

In 1976 the painter R.B. Kitaj RA curated for the Arts Council at the Hayward Gallery in London an exhibition titled The Human Clay. It consisted very largely of drawings from life by a selection of figurative painters of that time and was explicitly intended to reassert the importance of a figurative and humanist art in the face of what Kitaj saw as the increasing dominance of abstract, minimalist and conceptual art. In his catalogue essay for the exhibition he identified a group of painters that he named the School of London. They included Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, who were clearly chefs d’école, as well as Frank Auerbach and others. As I recall, the show was greeted with a mixture of bafflement and indifference.

But Kitaj was not alone in his feeling that figurative painting was being neglected by the art world powers. A few years later, in 1979, David Hockney, long before he became an RA (he was elected in 1991), gave an interview to the Observer in which he lambasted the Tate Gallery, and in particular its then Director, Norman Reid, for what he saw as its culpable neglect of figurative art. It was not Reid’s job, argued Hockney, “to decide what is significant. That will be decided in the future... that will be clear in the year 2000”. As a junior curator at the Tate at that time, I remember the row that ensued.

It has taken a little longer than Hockney thought, but this spring Tate Britain is putting the record straight by staging a major exhibition of British figurative art of the 20th century. Titled All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life it broadly embraces Kitaj’s School of London but looks back to origins in the early 20th century and follows the story up to the present day. All Too Human quite rightly confirms Bacon and Freud as presiding geniuses.

But surely, you may be thinking, the stature of those artists at least was already apparent back in the 1970s. Well, not everywhere. During Norman Reid’s directorship, from 1964 to 1979, the Tate Gallery bought only one small, admittedly superb, painting by Bacon (Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1966) and one, even smaller, by Freud.

We can now see in this show that these artists were not simply traditionalist or reactionary but were creating a figurative art that was also modern. They did so in broadly two ways. First, they were "painterly": their work was about the paint itself and the forging of the final image through the process of applying it. This emphasis on the medium is one of the essential defining characteristics of modern painting and was definitively summed up by Bacon himself in his famous remark "the image is the paint and the paint is the image". Secondly, they had a vision. They were exploring what it is to be human in a modern industrial society, especially one racked by two world wars and in which it was increasingly hard to believe in God.

In addition to this general existential angst, a painter like Bacon wrestled with homosexuality and homoeroticism, to powerful effect – Hockney once pungently remarked of Bacon’s male nudes that “you can smell the balls”. Artists like Stanley Spencer RA and Lucian Freud addressed head on, with unprecedented frankness, the nature of male heterosexual desire, and the fact of the body as simply flesh. More recently Paula Rego RA has created extraordinarily powerful and profoundly disturbing images of the hidden tensions, sexual and psychological, of family life. Cecily Brown meditates on the role of the erotic in art history and casts an ironic eye on the male nude. Cultural identity lies at the heart of the haunting work of the youngest artist in this show, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

The Family, 1988

Boy with a Cat, 2015

10pm Saturday, 2012

All Too Human takes as its point of departure the early 20th-century nudes of Walter Sickert RA, whose uningratiating tastelessness seems extraordinary for its time. One of the reasons Bacon and Freud failed to reach a wider audience in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s was that even then their work was seen by many as being in bad taste. They were of course simply confronting reality, of which, as T.S. Eliot famously reminded us, humankind cannot bear too much. And as Sickert himself insisted, “Taste is the death of a painter”.

Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1966

Girl with a White Dog, 1950-1

Nuit d'Été, 1906

Simon Wilson is a former Tate curator and a columnist for RA Magazine.

All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life is at Tate Britain, London, until 27 August 2018.

Related articles

In memoriam: Paula Rego RA

11 October 2022

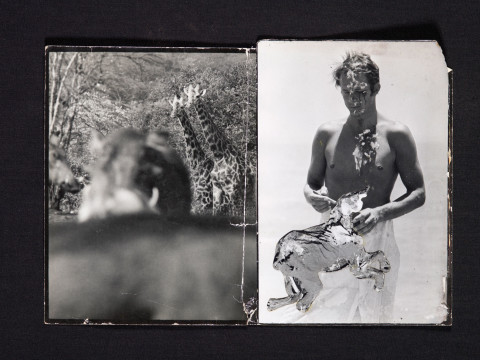

Francis Bacon: "I'm always labelled with horror"

5 April 2022

On safari with Francis Bacon

1 April 2022