Strike a pose: 250 years of life drawing at the RA

By Annette Wickham

Published on 6 February 2018

As our 'From Life' exhibition explores the past, present and future of representing bodies in art, we look back at the Royal Academy's 250-year tradition of drawing nude models.

Charles West Cope RA’s depiction of a life class taking place at the Royal Academy in 1865 is an evocative image that seems to sum up the conventions of traditional academic training. The young, exclusively male, art students sit at their easels in a semicircular formation, facing a nude male model who strikes a heroic pose on a dramatically lit platform. The atmosphere among the students appears to be one of intense concentration on their task, which is to render the figure before them in black and white on a standard-size sheet of paper. Although traditional, these conventions give rise to various questions, especially if one looks at the scene with no prior knowledge of art history. Why, for instance, is life drawing usually a collective activity? Why do the models invariably have to be nude? And why was the life class – for centuries – the mainstay of art education, even for artists who did not intend to spend their career depicting figures?

The answers lie in the Renaissance origins of life drawing. Like so many other innovations of the Renaissance, the evolution of the life class was inspired by the art of the classical world. As more and more ancient Greek and Roman statues emerged from excavations in Italy and beyond, it was immediately clear that their naturalistic yet highly idealised forms were the work of artists with a thorough understanding of the human body. Direct observation and study of the figure, Renaissance artists concluded, were the key to achieving similar results or even surpassing them. Michelangelo, in particular, was a prolific draughtsman whose surviving works include many striking figure studies and preparatory drawings for his major works.

Fancy trying your hand at life drawing?

Catch up with our live-streamed class that you can join from home.

Grab your pencils and paper and join #LifeDrawingLive, our online life drawing class led by renowned portraitist Jonathan Yeo.

It was a logical step for artists to study anatomy and to draw from nude models, despite moral qualms over both. Theoretical justification was provided by the Italian architect Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise On Painting (1435). He recommended the following process in preparing a figurative painting: "Before dressing a man we first draw him nude, then we enfold him in draperies. So in painting the nude we place first his bones and muscles which we then cover with flesh so that it is not difficult to understand where each muscle is beneath."

As Alberti suggests, life drawing was not seen as an end in itself, at least not for students. It was the ultimate stage in learning to draw, and was only to be approached after a prescribed course of preliminary studies, among them copying prints and drawings, drawing from ancient statues (or plaster casts of the same) and studying anatomy and the theory of perspective. This established progression is synthesised in an illustration in Diderot and d’Alembert’s eighteenth-century Encyclopedie. Students’ familiarity with the approved body types, poses and expressions of antique sculpture, so the theory went, would help them learn to ‘correct’ the quirks and aws of real human bodies – like a pair of rose-tinted, classicising spectacles. A famous classical model for the relationship between the real and ideal appears in a text by Cicero; the Roman orator and writer described the Greek painter Zeuxis making studies from five of the most beautiful women in his city in order to create one ideal woman to represent Helen of Troy. As Cicero relates: "he [Zeuxis] knew he could find no single form possessing all the characteristics of perfect beauty, which impartial Nature distributes among her children, accompanying each charm with a defect."

The life class developed in the studios of artists and craftsmen who took on pupils, but it assumed a more formal status in the first art "academy", which was set up by the painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari in Florence in 1563. Not primarily a teaching institution, the Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy and Company of the Arts of Drawing) also served as an artists’ association and, patronised by the influential Medici family, as a prestigious place of intellectual debate. Nevertheless, it proved highly influential in its codification of the hierarchical system of teaching drawing that was subsequently adopted in other academies that sprang up in Italy and, eventually, across Europe and the Americas.

The most significant national academy to open after the Renaissance period was the Académie royale de peinture et sculpture in Paris (later the Ecole des Beaux-Arts), founded in 1648 by King Louis XIV. Initially, the only practical instruction offered at the Académie royale was in drawing, making the life class the apex of the whole course. This emphasis on drawing stemmed from the humanist belief that the discipline was the foundation of all the visual arts. As Michelangelo put it: "Design, which by another name is called drawing ... is the fount and body of painting and sculpture and architecture and of every other kind of painting and the root of all sciences." Drawing – or "disegno" – also carried intellectual weight as the medium in which an artist’s creative power is first expressed and through which his or her thought processes are developed.

The Académie royale was granted a monopoly on the practice of life drawing, which greatly increased the method’s prestige and sense of exclusivity. A drawing by Charles-Joseph Natoire offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of its famous life class in action, although it is thought to be more of an 'idea' of a class than an attempt to record accurately the appearance of the room. Natoire, who later became Director of the Académie de France in Rome, included himself on the left (in the red cloak) as the tutor correcting students’ work. He would also have been responsible for setting the pose of the two male models apparently wrestling, perhaps in loose imitation of the famous antique statue The Wrestlers (Galleria degli Uffzi, Florence). The continuing importance of classical sculpture is also emphasised by the presence of casts after the Farnese Hercules, the Venus de’ Medici and other canonical works.

An anonymous "young painter at Paris" in May 1764 described the Académie royale life class: "there were at least 200 students, in a large hall ... all busy copying from a living man, who was placed naked in a reclining posture ... There are two rows of benches round the room; the highest for the statuaries [sculptors], the other for painters; every one has his own light placed at his right hand ... There are students here from all parts of the world." This British student had seen nothing quite like it at home. That is because a century of debate over the advantages and disadvantages of academic art education in Britain preceded the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768. Several less formal art schools and associations, some providing life drawing, existed in various parts of Britain before this date, but the Royal Academy was the first state-sanctioned art school in the country to be set up along the lines of continental academies. As such, it aimed to raise the status of British artists and equip a new generation of art students with the necessary skills to produce paintings, sculpture and architecture that would be on a par with the achievements of the Old Masters and their classical precursors.

Life drawing was crucial to this mission. When Johan Zoffany celebrated the foundation of the institution with his group portrait of the Academicians (1771–72), it is revealing that he chose to depict his fellow members gathered together in their Life Room. George Michael Moser, the first ‘Keeper’ (or head) of the RA Schools, is busy setting the pose of the model. Intriguingly though, closer inspection reveals that none of the artists looks as if he intends to do any drawing. It has been suggested that Zoffany was playfully echoing Raphael’s Vatican School of Athens and tapping into the idea of an academy as a place of debate. Even though they are not actually drawing, there is a sense of the artists’ shared pride at having finally secured a national academy in Britain to promote the practice.

The two curious oval portraits of women on the right of Zoffany’s painting are also significant. They depict the Royal Academy’s two female Foundation Members, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser. Unlike their male colleagues, they could not be shown attending the life class on the grounds of moral propriety, but Zoffany managed to shoehorn them in at one remove. The Academy’s attitude to women artists was only to become more problematic as time went on. Despite numerous women exhibitors at the annual exhibitions, no more female Academicians were admitted until the 20th century. Likewise, no female students were enrolled in the Schools until 1860, when Laura Herford applied, giving only her first initial and surname. It was assumed that L. Herford was male and "he" was offered a place. To their surprise, the Academicians found no written rule excluding women and Miss Herford was admitted. Others followed, but the women were initially confined to drawing casts and it was not until 1893 that they were allowed to draw from the male model – and then only if he was wearing a voluminous length of fabric thoroughly wrapped around his bathing trunks.

There was one role in which a woman was welcome in the early days of the Royal Academy: as a model. This was a significant departure from continental academic tradition, which focused exclusively on the male figure, following the Renaissance theory that upheld the male body as the "perfect" measure of all things (epitomised by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man). The Royal Academy preferred to follow the tradition of its less formal predecessors in London, including the private drawing school run by William Hogarth, which had always featured models of both genders.

Enjoyed this article?

This article is an extract from the first publication to question the meaning of working from life today. Artists Working From Life brings together interviews with 19 contemporary architects, painters, sculptors and conceptual artists to offer unexpected and inspiring viewpoints on a deeply rooted artistic tradition.

Enter FROMLIFE20 at checkout to claim your 20% discount.

Once it was taking place in a group setting at an official teaching institution supported by the King, the practice of drawing from the female nude became more socially acceptable. However, the Academy stipulated that students must be over 20 years of age or married to attend when a woman model was sitting. Despite this, behaviour was sometimes problematic. Although women were paid more to sit – as "shame" money – they were often assumed to be prostitutes and treated with less respect than the men. A depiction of the life class by the caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson hints at this attitude. (Indeed Rowlandson would know, having been almost expelled from the Royal Academy Schools for firing a pea shooter at a female model.) Similarly, the painter James Northcote RA recalled that although students were absorbed in their work during the class, some would "watch the women out" at the end. He added that certain young men had even been "lured into a course of dissipation and ruined by such connections".

In Rowlandson’s depiction, one of the artists – on the left, wearing an apron – appears to be painting instead of drawing. This again deviated from strict academic tradition but it was sometimes allowed in the RA life class, depending on the teacher. Records suggest, though, that painting was generally considered a practice that "seduced" students away from draughtsmanship and, as such, was only recommended at an advanced stage. Painted life studies also tended to raise moral hackles. Even a series of impressive flesh-toned chalk studies by William Mulready RA were denounced as "vulgar" and "bestial" by the critic John Ruskin. Queen Victoria disagreed, however, and bought one.

Seated male nude, mid-1850s

Standing female nude viewed from the back, 1850s?

Standing male nude, February 1859

The variable approach to life drawing at the Royal Academy was a direct result of the teaching system that had been put in place at the outset. There was no specialist teacher for the class, which was overseen instead by a series of "Visitors". These were nine Academicians elected annually, each to take a turn at teaching the class for a month. The intention was to avoid the students being overly influenced by one particular artist or style. The RA’s founding President, Sir Joshua Reynolds, felt that this had been a problem at some earlier academies, remarking that one of the great advantages of the new Academy was that it had "nothing to unlearn".

Classes were two hours long and models often held the same pose for several nights in a row. Luckily an hourglass was always on hand to ensure they had regular breaks. The Visitors set the pose of the model and some would watch over the class closely and correct drawings. Others, notably Mulready and William Etty, also taught by example, sitting down and drawing among the students. Mulready wrote: "I think it is beneficial to the students for the Visitor not only to say, 'Go in such a direction', but to go in that direction himself." Some Visitors, however, more or less opted out. The Victorian painter Sir Edwin Landseer, for example, was told off by his father, the engraver John Landseer, for reading Oliver Twist while his students drew. This situation was eventually to draw heavy criticism from commentators, the press and even the government, yet many students appreciated the relaxed approach, which they felt was a form of "wise neglect", and the Academy continued to run the class this way until the 1930s.

Certain Academicians attempted to enliven the experience of academic life drawing. John Constable set up a bower of greenery in the Life Room to aid the representation of the model as Eve in the Garden of Eden. William Etty devised a "living picture" with several models posing as Venus Sacrificing to the Graces; the Morning Herald described the scene, noting that it raised the "enthusiastic feelings" of the students "almost to ecstasy". Others pursued less dramatic methods. Thomas Stothard, for instance, developed an approach similar to the exercises that often feature in life classes today. While the model held a pose, Stothard – as Visitor – moved around the room taking different viewpoints and making small rapid sketches in a variety of media. Advanced students may have been encouraged to do the same. J.M.W. Turner, for one, produced drawings that were very similar to the sketches of Stothard, one of his teachers at the RA Schools. Turner appears to have followed his RA teachers closely; one of his Academy life drawings, now in the Tate collection, is also a close match for one by James Barry (Visitor from 1794 to 1795) in the RA Collection.

Studies of a seated female nude, c. 1800?

A Seated Male Nude with a Staff and with Right Arm on Head, in a Landscape Setting, c. 1794–95

Male nude sitting on a rock, c. 1790s?

During the nineteenth century other art schools emerged in Britain with very different approaches to life drawing. Founded in 1837, the Government School of Design (later the Royal College of Art) originally aimed to offer designers and craftsmen a thorough grounding in drawing and, as a result, promoted study from plaster casts of natural forms, ornamental designs and fragments of architecture and sculpture above life drawing. Conversely, the Slade School of Art, founded in 1871, was intended to train fine artists, and recommended "constant study from the life model", in the words of its first professor, Sir Edward Poynter Bt PRA. Slade students did begin their studies with a short stint of drawing plaster casts, but drawing and painting from the live model were the main focus of the course. Close observation was encouraged but studies did not need to be laboured to be considered "finished". The Royal Academy Schools belatedly followed suit, reducing the amount of time students had to spend drawing the (by then dreaded) casts, and introducing a broader curriculum with practical tuition in painting and sculpture.

In the twentieth century, however, life drawing also began to suffer from its elevated status within the academic canon. It had always had its critics; William Blake, for instance, had reportedly dismissed the static productions of the RA life class "as looking more like death, of smelling of mortality". By the 1960s, when state art education in the UK was being overhauled, this sense of its staleness had spread. Jon Thompson, who studied at the RA in the 1950s, was not alone in objecting to the practice of life drawing as "an ideologically loaded tool for making students conform to a certain philosophy of art". The traditional art-school curriculum of practical tuition, including life drawing, was entirely dismantled to be replaced by the more theoretical focus of the new Diploma in Art and Design. Ron Bowen, Reader Emeritus at the Slade, has stated: "Observation simply ceased to be of interest to most students and tutors. Even here, where the life class has remained central in the education of students, its role was challenged." Being outside the state system, the Royal Academy continued with its life class nevertheless and all students – despite being postgraduates – were expected to attend for at least a term. The redundancy of this pursuit, at least for some, is conveyed in a c.1979 portrayal of the Life Room by Helen Clapcott.

The Royal Academy eventually dropped compulsory life drawing, though it remains an option for Schools students, and practical courses are now offered to the public, including sessions where participants draw from life using iPads. Significantly, the Academy’s historic Life Room has been retained, set up with its rows of semicircular, paint-dashed benches and staffed with the apparatus of a traditional art school: anatomical figures, busts of Roman emperors, heavy velvet drapes and a formidable set of spotlights. It is also used by students as a place for meetings and lectures, parties and performances, installations and exhibitions.

And as life drawing has become disentangled from its historical academic context, it has been gradually reinvigorated, as is demonstrated by projects like Jeremy Deller’s Iggy Pop Life Class (2016). It has even been reintroduced in some art colleges. Bryan Kneale RA, as the first Professor of Drawing at the Royal College of Art, described how he encouraged students to try life drawing, advising them to approach the practice of drawing the model "from as many different viewpoints, physical and philosophical, as possible". Life drawing is now less about achieving a heroic, classical ideal and more about the quirky, the individual and the vulnerable, an exploration not only of the human form but also of the human condition. As Henry Moore put it: "You can’t understand life drawing without being emotionally involved ... It really is a deep, long struggle to understand oneself."

Annette Wickham is the Royal Academy's Curator of Works on Paper.

From Life

This exhibition looks to the past, present and future of the artistic process of life drawing – from the 18th century Academy to tomorrow's innovations in virtual reality. What does it means to make art from life? How do artists today observe and represent bodies? How is the practice evolving as technology opens up new ways of making and seeing?

Related articles

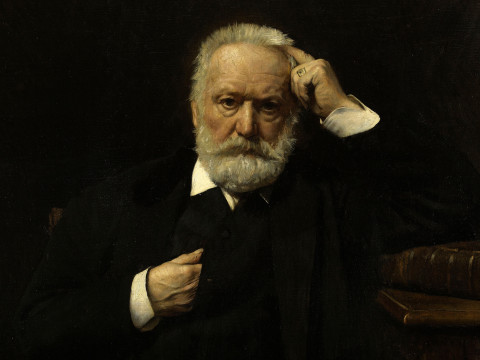

3 things you didn't know about Victor Hugo

14 March 2025

Documentary: inside 'Gauguin and the Impressionists' exhibition

6 December 2021

Nature and myth in art

30 August 2021

Saturday Sketch Club: drawing into the abstract

26 June 2021