In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

By Christopher Le Brun PPRA

Published on 30 April 2024

Christopher Le Brun PPRA remembers the painter’s generosity as a mentor and his inspirational independence as an artist.

From the Summer 2024 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

In 1973 William Coldstream persuaded Mick Moon to move from teaching at Chelsea School of Art to become a Senior Lecturer at the Slade. I was then in my third year of the Slade’s Diploma in Fine Art. The teaching staff was extremely varied in terms of different outlooks and traditions. First, the so-called Euston Road painters – Coldstream himself, Euan Uglow and Patrick George – representing a figuration that was essentially English, aiming for truth through observation. Another group, including Bernard Cohen, Tess Jaray and Malcolm Hughes, were abstract painters or Constructivists who relished the possibilities of new materials and processes. A further group comprised filmmakers and performance artists, as well as a charismatic lecturer in a grey boiler-suit, who taught Marxist art history.

To the problem of working out one’s personal and intellectual identity, Mick brought his professional experience and some answers to the unspoken question: how does an artist live? His career was then very much in the ascendant, summed up by his inclusion in the major survey ‘La peinture anglaise aujourd’hui’ at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Mick’s studio was on the top floor of Howard Hodgkin’s house and he and his circle were figures of some glamour. It was refreshing to hear his and John Hoyland’s un-academic anecdotes of what artists really do, deployed in gentle mockery against art school activists who were telling us what artists ought to do.

I’m particularly grateful that he introduced me to Ian Stephenson, who invited me to

join his postgraduate MA course at Chelsea. I had further reason to appreciate Mick’s encouragement and interest when, as a selector, he chose me for a group exhibition at the Serpentine in 1979, when I was given a gallery to myself.

Mick had the rare honour of a solo show at Tate Gallery in 1976, which was followed by the golden year of 1980, when he received a major Arts Council award and also first prize for his painting Box Room (1980) at the John Moores Exhibition in Liverpool. Box Room was grand in scale, richly coloured and inventive in technique, a painting managing to be both declamatory and inward and summing up his aesthetic concerns to date. Part painting, part assemblage, the colour and rich texture was cast and printed rather than being directly applied with the brush. The subject is essentially his studio and stands out within the long withdrawing tide of Cubism, showing his strong and unfashionable identification with the contemplative Georges Braque, rather than the showman Pablo Picasso. Braque’s late paintings of the 1940s and 50s depicted the studio as a place that, while private and personal, could be capable of producing imagery universal in implication. Both Braque and Moon shared that acute consciousness for touch and surface that a natural painter has, and that being so innate, has little traction in the way of messages for a general social sphere. This conviction for what was authentic informed his art and his teaching: the constant reminder that behind the door of the studio is always the solitary artist with no-one to depend on except themselves.

I think of him as an artist first and his manner, laconic and unimpressed by fashion, serves to highlight how much many art schools have changed over the years. When I try out the names of famous artists whether modern or historic, I find it difficult to picture them amongst the institutional working groups and research assessments. I also owe it to Mick to ask who the carefully worded policy statements are for. Do prospective students ever read them? They are more likely to be looking for risk and adventure. In any case, the muse of art is notoriously indifferent to virtue.

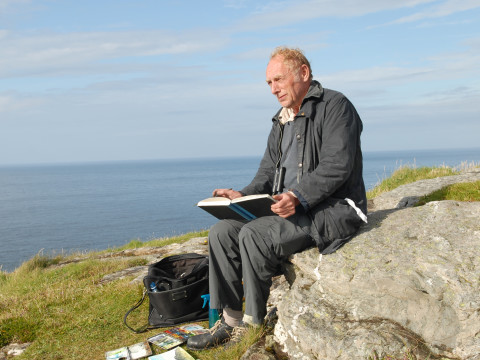

A period of fresh and inventive printmaking by Mick was followed in a later phase by predominantly tonal work of great subtlety and some melancholy, where the motif is often isolated against a ground. Texture forms the atmosphere, becoming finally a signature note. There are memories (perhaps of childhood) of the coast at Blackpool and there is always water. Somehow apparent opposites are reconciled and there is quietude. Painting is sensuous intelligence embodied. Time and quiet will bring the sympathetic observer some trace of those hard-won insights and feelings which were once consigned to material by Mick’s living hand.

Christopher Le Brun PPRA is an artist.

Related articles

Five Brazilian cultural icons from the 20th century

28 February 2025

A love letter to the gallery gift shop

18 November 2024

Painting the town: Florence in 1504

15 November 2024

Moving a masterpiece

7 November 2024

In memoriam: Norman Ackroyd RA

20 September 2024