"I only do something if I’m afraid of it, because that’s the whole point" – an interview with Marina Abramović

By Sinéad Gleeson

Published on 24 August 2023

In this long-read, performance art pioneer Marina Abramović speaks to Sinéad Gleeson from her New York home, ahead of her long-awaited show.

Born in Belgrade in the former Yugoslavia in 1946, Marina Abramović is something of a matryoshka figure: an endurance artist within a performance artist within one of the most significant art practitioners of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Abramović’s life began in the aftermath of the Second World War, amid the beginnings of Tito’s autocratic rule of Yugoslavia. She grew up in a household stifled by discipline and militaristic rules: her father was a general and both parents had been partisan fighters against the Axis Powers during the war. Time was to be obeyed, as was a 10pm curfew. Abramović folded herself into this strictly scheduled life, yet found ways to rebel and make art. The body became her primary medium, but the malleability of time too. The performances from the 1970s that would make her name were conceptual and corporeally centred, emerging within a decade rooted in political and social upheaval. Abramović has since consistently pushed at boundaries – physical, geographic, of identity – with work performed within the confines of the clock.

I really think that I was born an artist. I don’t remember anything else as a child other than having a pencil and drawing.

Marina Abramović

The exhibition at the Royal Academy collates 50 years of work. Mindful of her legacy, the artist has been training a new generation of artists in the Marina Abramović method, to reperform her past works. Four significant works are reperformed in the galleries, not by the Serbian but by emerging artists, with other past pieces represented by a substantial body of films and photographs, together with installations, sculptures and drawings. These are organised thematically rather than chronologically. Key concerns recur – spirituality, pain, the connectedness of the human and non-human – presented as though the artist’s life depends on it.

The first section of the show unites two of her most famous performances: 1974’s Rhythm 0 and The Artist is Present, from 2010. In the former, an audience unsure of its boundaries and the nature of performance art could choose one of 72 objects to use on Abramović, who stood motionless and unspeaking for six hours. The tone shifted from curious bystanders offering her flowers to someone pointing a loaded gun at the artist. Thirty-six years later, when Abramović was well-established and much-fêted in the art world, The Artist is Present attracted a different kind of audience – admirers (including Bjork and Lou Reed) well-versed in what she had endured in the name of art. Rhythm 0 amplified the audience’s voyeurism, but The Artist is Present created a symbiotic link, an exchange of energy Abramović believes is vital to fuel a work of durational art. In MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day for nearly three months facing whatever stranger occupied the chair across from her. There was no tactility – and no guns or knives – but it felt more intimate and exposing.

While her body is the locus of the work, it robustly resists the male gaze, antagonising its assumptions (and entitlement) to refined representations of beauty. In Art Must Be Beautiful / Artist Must Be Beautiful, Abramović violently brushes her own hair, the antithesis of a siren, more a banshee with a comb. Entire canonical narratives of pain are embedded in our ideas of illness and immobility, which suggest a lack of control, or an unasked-for sense of discomfort. Abramović’s pain has autonomy. It is created and directed by her. The primacy of flesh and blood parallel the concepts of sacrifice and Christian suffering. Abramović’s metamorphosis from person to artist mid-performance is its own transubstantiation. In turn, an audience experiences a transference of sorts – the artist suffers for her art, but also for the viewer. Our complicity is part of the process. From the loaded gun in Rhythm 0, to the choreomania of Freeing the Body (1975), which involved dancing for hours to African drums until collapsing, Abramović’s own complicity is with the total obliteration of limits.

In the Royal Academy, several of the ‘Rhythm’ series are located beside pieces made with the German artist Ulay, revealing an overlapping resonance of commitment and process. They met on 30 November 1975 – their shared birthday – and became professionally and personally entwined. Their combined output over 12 years was not just a series of collaborative performances, but an articulation of their relationship and its hybrid energy. For Abramović, it was ‘That Self ’; Ulay called it the ‘Third Space’, a binary that united their personalities and artistic selves. In Rest Energy (1980), first performed in Dublin, each gripped a taut crossbow, the arrow pointing at Abramović’s heart, and small microphones were used to amplify their heartbeats. It lasted just over four minutes, but Abramović declared that it felt like ‘forever’, its duration telescoped in sensation and emotion.

Rest Energy, 1980

Imponderabilia, 1977

Rhythm 0, 1974

Abramović’s practice commits to taking up space, to placing her body in galleries and rooms and eschewing privacy and comfort: in the raised rooms of The House With The Ocean View (2002) – which will be reperformed in the RA exhibition – where she lived for 12 days and the ladders offering escape had knives for steps; in the airless heat of a Venetian basement scrubbing animal bones and singing folksongs for Balkan Baroque, which won the Golden Lion at the 1997 Venice Biennale; at MoMA where she sat, back-breakingly, for 716 hours. Paradoxically, the performances rooted in ephemerality have been the most indelible of all her works.

That this is the first solo show by a woman in the RA’s Main Galleries is significant. Abramović’s maverick work is both an antidote and riposte to three centuries of her patriarchal predecessors. It ushers in embodiment and spirituality, politics and confrontation. Behind the scenes, Abramović has worked closely with the curators and perfomers of the pieces. Even if the artist is not physically present, decades of Abramović’s work will impose its singular energy on the space.

Sinéad Gleeson: Your RA show was first planned for 2020 but postponed because of the Covid pandemic. In the past, you’ve spoken about how we don’t have any time to sit still. And that ideas come out of stillness. Given the show has probably undergone some changes, I’m wondering, what did that pausing, that stillness, alter in the show?

Marina Abramović: I think Covid postponing the show for three years was a blessing from God. I am so happy this happened because in 2020 the show would have been something completely different from what it will be in 2023. Those three years gave me so much time to reflect, and basically to change everything – this is quite literally not the same show. Working with the curator Andrea Tarsia was wonderful, because we said, “Okay, let’s completely switch off everything, every idea we have had until now, and start with a blank slate.”

And now the exhibition is actually my dream, because it shows people what I’ve been doing for all these years. The public mostly know me as a performance artist doing performance work, but you can’t place me in that box. Every time you place me in one box, I jump out of it into something else. I have an enormous body of work that is not performance: my ‘Transitory Objects’ that people interact with; the photographic work, the Polaroids; the paper rubbings…

SG: A lot of your early work was sound based, wasn’t it?

MA: Yes, the sound work we won’t show at the Royal Academy, but my work did start with sound. It was sound that brought me to use the body: through that I moved into performance. But it is important that I say that this show is not a retrospective in any sense. This is absolutely not a retrospective because we decided that my old work has to have a conversation with the new work, and it does. I’m constantly going backwards and forwards, thinking about really old work from the 1960s as well as new work.

Originally, I wanted to call the show ‘Afterlife’ but we decided to call it as all the other Academicians’ shows before me: just the name ‘Marina Abramović’, like ‘Antony Gormley’, like ‘Ai Weiwei’. The fact that in 255 years, there has been no woman showing solo in this big space makes it a huge responsibility. This is one of the reasons that I absolutely want to hold a Women’s Tea Party at the RA, a private event just for the girls, you know. I want to invite young artists. I want to invite writers, scientists, politicians, women from all kinds of fields, actresses. I want to invest my own energy, to give them my work and my life through the show, and then have tea. This is the fastest sponsored party I’ve ever organised. We immediately found a sponsor – it looks like the English really love tea.

SG: I’m fascinated that in your work, the body is like a klaxon. It’s an act of resistance, a political tool, a manifesto. Why has the body been so central? You didn’t become a photographer, you didn’t become a painter – it was the body that was your process.

MA: This, again, leads to the sound work, but it actually goes back earlier than that. When I started painting as a kid – when I had my first show, when I was 14 years old – I was painting dreams. The dreams were something given to me, so it was so easy: I would dream, then wake up in the morning and then paint the dream. And in most of the dreams I was part of the dream, so I was painting myself in different situations. After that I went in a different direction. I painted car accidents; something about their energy was fascinating, the crash.

I turned to the body at the Academy of Fine Arts [in Belgrade]. There was one model who I always painted from the back. She was a very large woman, very monumental. And I loved her body, because it reminded me of landscapes. In the body, I saw the mountains and hills and rivers. And I painted her for four years at the Academy, just from the back, like a landscape. I also painted clouds, clouds above her body. Then one day, she said to me that she was leaving, she was finishing her career in modelling. It was her last day when she told me. So I asked, “Can you turn to me so I can paint your face for the first time?” And when I painted her face, I had an incredible realisation: it was so empty. There was just nothing there, there was no landscape, there was nothing. I could not connect with it.

After she left, I started only concentrating on the clouds, all different kinds – ominous clouds, clouds attacking bodies, black clouds. In my free time I would go into a field and lie on the grass and observe the sky. One day I saw a totally blue sky, not even one cloud, and out of nowhere came these ultrasonic military planes and they made this whoom, you know, creating lines of clouds in the sky like a very abstract drawing. And it was completely fascinating, how this drawing swarmed and then disappeared, with the sky then blue again afterwards. I realised, why do I have to go to my studio and paint something two-dimensional? I could use the air. I could use fire, water, the earth, the elements.

I went to the military base and I asked people there about the planes, and they called my father, who was a General – a national hero in the Second World War, blah blah blah – and they said, you know, can you get your daughter out of here? I was 17. Then I started getting more crazy ideas. One was to go to a bridge and put very large speakers on it with the sound of the bridge falling down. I had to go to City Hall to ask for permission. They absolutely forbade it, because the vibration can make the bridge fall.

Then I said, okay, but what about my own building? My family lived on the third or fourth floor, so I put the speakers all around with the sound of the building falling down. Everybody ran out thinking “Is this bombing?” It lasted for 15 minutes. That was a huge scandal. Then I saw a very poor little tree in the front of the Student Cultural Centre and I thought, what if I put a speaker here with the incredible sound of tropical birds, so that the sound completely changes the environment into some kind of beautiful South American landscape? I did that – that was allowed.

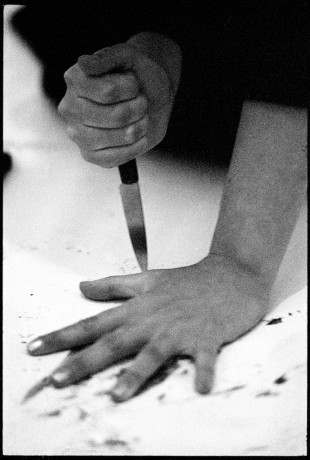

As this sound work evolved, I started involving my body. And my first work was based on assault, Rhythm 10 [in which Abramović stabbed a knife between the splayed fingers of one hand]. The first performance was in 1973, I think. This was performed with 20 knives, with the sound recorded. Every time I stabbed my finger with a knife and cut myself, I would change to a new knife. In the second part of the work I listened to the recording, and repeated the exact sequence of stabs, the entire game, one more time. I concentrated on the recording, listening to my groans, in order to make the same mistake at the same time. The idea was: how can I put a past and future mistake together in one? It’s crazy idea. But I did it.

Rhythm 10, 1973

Rhythm 10, 1973

Rhythm 10, 1973

One important thing about that piece was that it was the first time I was with my body in front of an audience. That experience of energy, of some kind of magic that I never could have in my studio painting – it was like, wow, something happened there. It created a space which was so together: the public and me, united in one thing. Nobody was breathing until the performance finished. I knew then that this was my tool, the body was my tool.

SG: How huge was that revelation? Not just that you could utilise this symbiotic energy in your performances, but in how it changed you as an artist?

MA: Until that time, I was incredibly timid, I was introverted. I could never have taken my clothes off in public. But once I had done this performance, something clicked. It was not “poor Marina”, it was really “highest self Marina”. Even now, you know, it’s not easy for me to take my clothes off in front of friends, if we’re going to swim. But if I have to do that in the front of the public, it doesn’t matter if I’m old, it doesn’t matter if I’m young, it doesn’t matter if I’m fat or whatever, I present the body as a universal human body, free from all of this judgement, and that is an incredible freedom.

You really start to understand the soul, as when you write or create or perform, you really do it from the highest self. But that energy takes such concentration. You can’t maintain it for a long time. And then you go back afterwards to your, you know, little self.

SG: It must have been very difficult, and maybe frightening, for you to make that kind of work in the 1970s. Were you aware of how groundbreaking it was?

MA: I was very aware of this. I was constantly feeling like the first woman on the Moon. First of all, the things that I was doing were against my own family. They were questioned at the Communist Party’s meeting: how can a General’s daughter be allowed to burn the Communist star in the square [Rhythm 5, 1974]? At the same time, I still had to live with my family, because under Communism, nobody had their own place. Whatever I did, whatever performance, I had to be home by 10pm in the evening. This was the rule.

The newspapers said my work was “scandalous”, that I should be put in a mental hospital, that this is not art. My professor was ashamed even to see me. I was a complete disgrace. I don’t know why I had this incredibly strong vision, that I knew I was on the right path. There was something in me, my fire, total intuition, that I had to do this. And you know, it is 50 years later now. And I was right.

SG: The critic Jovana Stokić wrote “Abramović has never left the Balkans”. I wonder, do you agree with that? And if you hadn’t come from the Balkans, would you still be an artist?

MA: I really think that I was born an artist. I don’t remember anything else as a child other than having a pencil and drawing. But definitely, it doesn’t matter where I am, I have Balkan in me very strongly, that feeling of identification.

I was born there into such a strange Communist background. A mother who was all about discipline and control, and then a father who felt that your private life was not important – what was important was the Communist cause that you had to fight for. And a grandmother who was highly religious, who was most of the time in the church following all the rituals of the Orthodox Church, which really influenced me later on to become interested in Buddhism, shamanism and spiritualism. Also a great-uncle who was literally proclaimed as a saint [he was head of the Serbian Orthodox Church], so I had two national heroes in my family – I mean, this is crazy.

This combination formed me deeply. I have no idea what I would be without it because this combination is in me. I have never wanted to go back to when I was young, because I suffered too much then. But now I am in this position of wisdom, of seeing life in a different way, with lots of joy and pleasantness and humour – from this position, I want to go back to my roots.

SG: I remember reading in your autobiography, where you said how much fear was built into you, by your parents and others surrounding you. Does fear have a place in your work?

MA: Yes, a big one. If there’s something I would like to do, I don’t do it. I only do something if I’m afraid of it, because that’s the whole point. If we always tend to do things that we like, then we are creating the same pattern, making the same mistakes again, and we never get out into unknown territory.

I remember when I first had the first idea for The Artist is Present, I said to myself, “Oh my god, I’m crazy. How can I do this for three months?” But then I became obsessed. And it was so hard. It was supernatural to do this – to sit in front of thousands of different people, eight hours a day for three months. There were days when I thought I could not continue. But I did it. And this came out of the complete fear that I could not do it.

At the same time, The Artist is Present was my big chance to show the public the power, the transformative power, of performance art, by literally doing nothing – by just being in a space and being noticed. And then came this incredible thing: people sleeping outside the museum, standing there for hours to see the work. It had 850,000 visitors, which broke records for any living artist. And this was absolutely by being still, being the eye of the tornado.

SG: With that particular work at MoMA in New York, a lot of people posted clips of the performance online. Is there a conflict between wanting a performance to be ephemeral while wanting people who were not there to see it?

MA: First of all, in the early ’70s, recording was something that younger, radical performance artists decided you should not do. But I understood early on – and I was probably one of the few people in that period to realise this – that the record is important, the document is important. So I recorded the early works really well with photography, as there wasn’t access to video.

Then came this turning point, when I was invited to Copenhagen to do the performance Art Must be Beautiful / Artist Must be Beautiful. They told me for the first time that a video will be made, which was totally new for me. As soon as the performance finished, we went backstage to watch the video, and I looked at it completely horrified, because my work was looking like total shit. I said to the cameraman, “Where is the delete button?” and we deleted it in its entirety. I didn’t want this video ever to have a life, because it was an interpretation, his interpretation, and not my work. So then I said to him, “Now, can we put the camera on, and I will frame my face exactly as I want. You’re going to press the button and go out and smoke a cigarette.” Which he did. I recorded the entire piece and that is now the documentation of that work. After that, I understood the power of recording.

I don’t compromise – I tell the truth, I’m not bullshitting.

Marina Abramović

SG: Does the recording then become something of similar significance to the original live work?

MA: The same amount of time spent constructing the piece is spent deciding how the piece will be recorded, because this document stays forever. There will be recordings of The Artist is Present shown at the Royal Academy. That was so complex to film. I had the camera on my face all the time, and I had a camera on the face of every person sitting opposite me, and then I had the camera filming the two people at the table. It took months to edit. The editor had to go to Bali for a year to rest afterwards.

I’m always curious about technology and what is new. I made a Mixed Reality piece that was recorded with 32 cameras. When you wear the headset, it’s like I’m built out of dust, built out of energy. You can just walk through me. It’s quite frightening for me to look at myself that way. This technology has a future. It’s better to have Mixed Reality recordings than flat-screen videos. It is like three dimensions, and the way it immortalises the energy is fascinating.

SG: In the exhibition, four of your previous pieces are being reperformed by performers other than yourself. They are all physically demanding works – I understand that you have had a recent run of bad health. Is it hard for you to deal with that as you age? The idea that you won’t be performing as you have done before. Do you miss it?

MA: I don’t miss it because my opera, 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, has been touring for two years, and I’m performing on stage every evening it’s on. I create pieces like this that I can do physically, that are within my physical limits. I created an entire performance within Callas that I can perform in any bodily condition – even if I’m 80 or 90 – so that’s perfect. Why should I do things where I show my weakness? If I can’t do something, I won’t. I really want to have dignity in being old and seeing my limits. And I have the incredible pleasure of teaching the Abramović Method, training young artists, teaching things that nobody ever taught me.

The limits of the body are something that you very gradually come to understand. When I performed The Artist is Present I was 65. I could never have performed this piece if I was 20 or 30, for the simple reason that I didn’t have the kind of control of the self, the incredible willpower and the state of mind. You have certain stages when you can do certain things. Recently, I gave a performative lecture to people in Lithuania. They rented an entire basketball stadium for me, for 6,000 people – the largest audience I have ever had – and I not only talked about my work but also I had them perform. I asked them to stand up, to breathe, to create certain sounds or maintain complete silence. It showed how I can now work with masses of people and create experiences for them. So performance is changing and my role is changing.

Now [following an embolism] there is a new restriction in my life. For six months, I can’t take a plane. Usually I take a plane every two, three, five days. So this is an incredible restriction, not planned. To come to London, for the Royal Academy show, I must take the boat from New York.

SG: How important was it to have works reperformed in the RA show? Do you decide who the performers are?

MA: We have an entire team doing the casting because casting is very important. It is the same as a concert performance – you can have someone playing Bach badly or well. With pieces like Imponderabilia, where two naked performers form a doorway, that is easier to cast and train because it’s one hour per shift. But with a piece like The House with the Ocean View, which is 12 days long, and involves no food or talking, we cast people who I really know can do it, or who have done some of my other performances. The first time that work was reperformed I didn’t visit it when it began – I didn’t want my presence to change the structure of the relationship with the audience that the performer really deserved to have. But I came to see it on the fifth or sixth day. At that moment, standing in front of my piece, seeing it reperformed, I just cried. I could see my work live on without me. It was a big moment.

When I introduced the idea of reperformance, with Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim [in 2005], where I performed works by others like Joseph Beuys and Bruce Nauman, all of my generation was against me. They said, “We would never give our work to anybody else to perform.” But why? Your piece has to have life, and has to have new life. And even if people bring their own energy and their own interpretation to the work, that is better than the work being dead, dusty, just a bad video recording or a mention in the books. I feel a responsibility to put performance art, as the most transformative form of art, into the mainstream. To introduce the history of performance and share my methods. I’ve also created the Marina Abramović Institute to encourage a younger generation of performance artists.

SG: I’m slightly envious of some people who will walk into the Royal Academy – they’ll go along with a friend – and they won’t know anything about your work. How do you feel about a new generation of people discovering your work?

MA: I love that my work draws new audiences, and young audiences. When I made an opera, many people who came to see it had never been to an opera before, many were young. My generation just come to see if I’m still alive, whether I have done something shitty, or whatever. But the young give me so much love. I am not sure why I touch them. I think it’s because I don’t compromise – I tell the truth, I’m not bullshitting. That has reached them. The best criticism I heard was when Callas was at the Opéra Garnier in Paris. Two old ladies, probably my age, were coming down the stairs together, and they looked at each other, and said Mais c’est ne pas Classique. That’s not classic. That’s great. C’est definitely pas Classique!

SG: My last question. I have the impression that you are never going to retire, that you’re just going to keep on making art until the moment that you’re not here. Is there a sense that you’re running out of time to do what you want to do?

MA: That’s totally true. I am so full of ideas, and I love life and I love working. That’s really my big passion. I don’t have any plan for a pension, retirement. I don’t think the artist can. But this whole recent horrifying thing, when I needed an operation for a blocked artery – it was really life threatening. If I had taken a plane, I could have been dead. And I feel like, for some strange reason, it has given me a completely new beginning. Now everything’s ready for the show. We’ve done all the preparation work. The only thing I have to do now is to take the boat to the UK and get to the Royal Academy for the opening – and hold my tea party for women.

Sinéad Gleeson is a writer, editor and broadcaster whose books include Constellations: Reflections from Life (Picador). Her first novel will be published by 4th Estate in April 2024.

Marina Abramović takes place in the Main Galleries, Burlington House, 23 September 2023 – 1 January 2024.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Five Brazilian cultural icons from the 20th century

28 February 2025

A love letter to the gallery gift shop

18 November 2024

Painting the town: Florence in 1504

15 November 2024

Moving a masterpiece

7 November 2024

In memoriam: Norman Ackroyd RA

20 September 2024