Henrietta Maria: the queen behind Charles I's collection

By Erin Griffey

Published on 8 March 2018

Charles I might have had a keen eye for art, but his queen's eye was sharper and far more sophisticated. With the couple's extraordinary art collection currently on display at the RA, the consort's biographer Erin Griffey explores her life, style and legacy.

From the Spring 2018 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

When the French princess Henrietta Maria arrived in England at the Stuart court in 1625, she was just 15 years old and had never met her husband to whom she was married by proxy, Charles I. She made the journey from Paris with a vast entourage of servants and priests, with her trunks of diamonds and pearls, exquisitely embroidered dresses and richly decorated furniture, borne by a parade of colourfully caparisoned horses. Such an entrance set the tone for her stately magnificence and exceptional taste. The daughter of Henri IV and Marie de Medici, the Bourbon princess was never going to be short on opulent display.

Who was this extraordinary figure who, as England’s queen, won over the court and became a key patron of the arts, overseeing the hanging of some of the finest of Europe’s art treasures in her palaces, including Italian Renaissance paintings in the Royal Academy’s exhibition Charles I: King and Collector?

In 1625, being both French and Catholic, Henrietta Maria was particularly vulnerable to an English public that was deeply suspicious – if not outwardly hostile – to those most essential aspects of her identity. Her marriage to Charles had been a dynastic match to advance diplomatic ties between England and France, and negotiations had been particularly delicate because this was the first cross-confessional marriage of a Protestant heir to the throne to a Catholic princess. Pope Urban VIII, her godfather, provided the necessary dispensation and he inveighed her to advance the Catholic cause in England. For the Pope, her French family and English Catholics, there was every hope that she might convert the King, an aspiration that struck horror in the wider English population. If she managed to charm many at court with her sophistication and lively personality, she remained deeply divisive throughout her life, not just because of her French heritage and Catholicism but her perceived power over the King.

The couple’s first public appearance in London saw them in matching green outfits on a boat on the Thames. However, the relationship between the King and his Queen did not bode particularly well at first. She maintained strict religious devotions and spent extravagant sums of money on luxury goods. The King, for his part, dismissed most of her French retinue, sparking a diplomatic uproar. Charles’s dedication to his court favourite, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, certainly did not help the newlyweds. But their intimacy grew, and after Buckingham’s death in 1628 they developed a strong bond, both physically and emotionally. While their first child, a son, died shortly after birth, she would have eight more children, two of whom would become kings. Indeed, she was the most fertile of all the Stuart queens, providing stability for the dynasty.

If she fulfilled her primary royal duty as a consort, Henrietta Maria also proved to be profoundly loyal and was a strong advocate for her husband and later her son’s cause. While occasionally self-indulgent – during difficult times she was known to call herself miserable – and zealously self-righteous, she was a formidable force of nature. She was also a dutiful daughter and a devout Catholic. Her steadfast devotion was made all the more poignant by her separation from her husband for long periods during the civil wars.

In 1625, being both French and Catholic, Henrietta Maria was particularly vulnerable to an English public that was deeply suspicious – if not outwardly hostile – to those most essential aspects of her identity. Her marriage to Charles had been a dynastic match to advance diplomatic ties between England and France, and negotiations had been particularly delicate because this was the first cross-confessional marriage of a Protestant heir to the throne to a Catholic princess. Pope Urban VIII, her godfather, provided the necessary dispensation and he inveighed her to advance the Catholic cause in England. For the Pope, her French family and English Catholics, there was every hope that she might convert the King, an aspiration that struck horror in the wider English population. If she managed to charm many at court with her sophistication and lively personality, she remained deeply divisive throughout her life, not just because of her French heritage and Catholicism but her perceived power over the King.

If her position as mother to a growing brood of royal children and her close bond with her husband enhanced her power at court in the 1630s, her patronage also flourished during this period. Raised at the French court and au fait with ballet and court theatricals, Henrietta Maria was an enthusiastic patron of court masques, in which she performed starring roles. She played an active part in the commissioning of artworks, buildings, garden designs, furnishings and other luxury goods at court. Even if the King financed the bulk of the building works at her palaces, she approached the interior decoration of her palaces, and the gardens that surrounded them, with alacrity, as her own financial accounts attest. After all, she had an independent income generated through her jointure, or marriage settlement, totalling more than £28,000 by 1630, an immense sum. She also received several palaces as part of her jointure. Somerset House, Greenwich, Oatlands, Nonsuch, Richmond and Holdenby had all been settled on her by 1630, with Wimbledon allocated by 1639. This was royal living on a very impressive scale.

Her palaces were the subject of extensive renovations, more so even than the King’s, and she funded lavish redecorations of rooms, with Persian carpets, Mortlake tapestries, wrap-around silk bed curtains and inlaid cabinets, the floors strewn with fresh flowers. Her accounts show that she made payments to Inigo Jones, who designed her "House of Delight" at Greenwich. Notably, too, she retained the services of French garden designers, including Isaac de Caus, André Mollet and André le Nôtre. She even ordered flowers and fruit trees from France.

The paintings she chose for her palace interiors that are now on show in the RA’s magisterial exhibition include Correggio’s Holy Family with St Jerome (c.1519) at Greenwich and Jacopo Bassano’s Adoration of the Shepherds (c.1546) at Wimbledon. The Queen also had an affinity for Italian Baroque pictures by Guido Reni and Orazio Gentileschi, with her house at Greenwich decorated with three large history paintings by Orazio, including Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (c.1630-32) as well as an allegorical ceiling cycle. Religious pictures proliferated in her palaces and chapels, and family portraits were also prominently displayed. Ever the proud mother, she sent gifts of her children’s portraits as part of the customary exchange of family portraits amongst relatives.

Her lavish wardrobe seems to have been funded entirely through her own revenue. The ravishing silks, delicate ribbons and luminous jewels in her portraits reveal a woman of huge wealth as well as style. She maintained a French tailor, embroiderer and perfumer, as well as a veritable army of artisans and suppliers to ensure she was the best-dressed woman at court. Her style was widely emulated, as evidenced by the many portraits of Stuart ladies whose coiffures and clothes pay homage to their French queen.

Henrietta Maria remained centre stage during the civil wars, both as a source of blame for the problems and support for her husband’s cause. If she had experienced "miseries" at the expulsion of her servants when she had first arrived in England, the very public humiliations and financial hardships of the civil wars would engulf her. Her correspondence with Charles shows her active involvement in his approach to Parliament, the handling of his troops and the guarding of the royal children. As the fate of the crown became more uncertain and with her personal safety in desperate danger, she fled to France in the summer of 1644. She was never to see her husband again and news of his execution in 1649 came as a profound shock.

Paris would remain her "sad place of exile" until 1660, when her son Charles II returned triumphantly to be crowned king. She was euphoric at this dramatic change of events and returned to London the same year to showcase her ongoing relevance at court, reclaiming former palaces including Somerset House and her Jones-designed house at Greenwich. Somerset House was exquisitely renovated and refurbished, but the Queen had little time to enjoy it. During the summer of 1665, during a particularly virulent outbreak of the plague, she returned to France.

In her final years she divided her time between her château at Colombes and the convent she founded at Chaillot. Naturally, Colombes was furnished with a fine display of paintings, including portraits of her children by Van Dyck, as well as pictures attributed to Titian, Correggio, Perugino, Giulio Romano, Tintoretto, Andrea del Sarto and Guido Reni, as well as Holbein’s Noli me tangere (1528) and Orazio Gentileschi’s Finding of Moses (c.1633), both on display in the RA show. The pictures reflect her Italianate tastes and some of those at Colombes, including Holbein’s picture, were sent to England after her death and remain in the Royal Collection. She was an ardent champion of her eldest son, whose portrait hung prominently at her French château, where she died just before her 60th birthday.

Although most of her former palaces have now been demolished, a sense of Henrietta Maria’s importance as a queen consort and patron survive in her elegant retreat at Greenwich. It is fitting that her main palace, Somerset House, continues to thrive as a centre for the arts. Henrietta Maria’s power at the Stuart court reached far beyond the roles of consort and mother. Her foreign heritage and Catholic religion meant that she played a role in international diplomacy and religious issues, but she also remained an indomitable advocate for the Stuart cause, a sophisticated patron of the arts and a paradigm of fashion.

Erin Griffey is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Auckland and author of On Display: Henrietta Maria and the Materials of Magnificence at the Stuart Court.

Exhibition organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust.

Join us to hear more from Erin Griffey on the Queen's influence

Learn more about the assertive, sophisticated, fashionable queen as Erin Griffey gives a talk on the monarch's patronage, taste and networks.

Related articles

Five Brazilian cultural icons from the 20th century

28 February 2025

A love letter to the gallery gift shop

18 November 2024

Painting the town: Florence in 1504

15 November 2024

Moving a masterpiece

7 November 2024

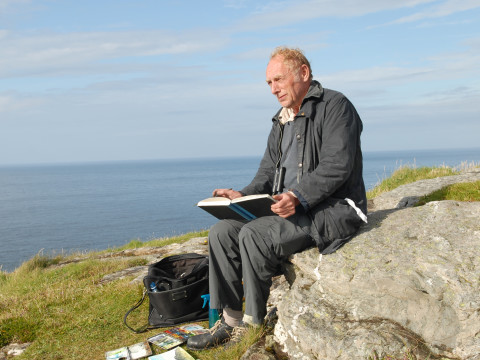

In memoriam: Norman Ackroyd RA

20 September 2024