Joseph Cornell: Pioneer of assemblage art

By Deborah Solomon

Published on 20 May 2015

Joseph Cornell created curious worlds of long ago and far away in his boxes of found objects. We examine the work of this American trailblazer ahead of his RA exhibition.

From the Summer 2015 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

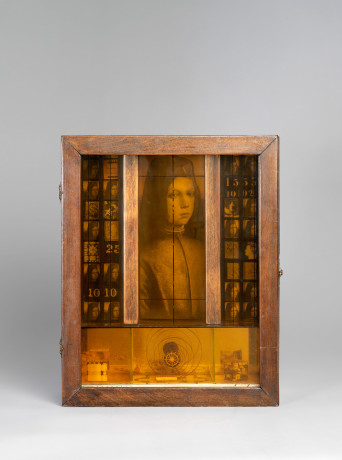

Joseph Cornell was an unrepentant homebody, a meek, monkish, well-read man who never spent a night away from home. He is celebrated for boxed assemblages that extract an inexplicable poetry from arrangements of humble objects and images – cork balls, metal springs, reproductions of parakeets and Renaissance portraits. Revered in America as one of the most original artists of the mid-20th century, Cornell remains sorely under-exhibited internationally. That changes this summer, when Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust opens at the Academy.

The "wanderlust" in the exhibition’s title is presumably intended with sincerity and irony in equal parts. The word, of course, derives from German and denotes a yearning for distant travel, preferably along the trails of craggy alps and primeval forests. But Cornell, who died in 1972 at the age of 69, favoured rambles close to home through the shop-lined streets of New York. For most of his life, he lived with his widowed mother and disabled brother in a narrow, wood-shingled house at 3708 Utopia Parkway in Queens, a residential borough beyond Manhattan. When he confided to feelings of wanderlust in his diaries, which he often did, he was referring to his desire to escape the house for a few hours.

On the other hand, Cornell did travel widely in his work. His boxes quietly reference the culture of long-ago European capitals, and allow the past to make itself vividly present. Many of his works were conceived as direct tributes to actresses and ballerinas, both living and dead, who were the subjects of his intense, inevitably unrequited crushes. If his work allowed him to crystallise his wide cultural and scientific interests, his jaunts to Manhattan were an inextricable part of the process. On a typical outing he scouted for source material, a tall, gaunt man disappearing down the aisles of the now-defunct bookshops lining Fourth Avenue. He usually stopped for lunch at midtown coffee shops, where he was likely to take pity on a careworn waitress and jot down related notes on his napkin.

Returning home to Queens, his top coat grazed with dust, Cornell filed away his notes and trouvailles in his cramped basement studio. Photographs taken by the artist Harry Roseman in the late 1960s offer a moving glimpse of the room, with its cardboard storage boxes heaped to the ceiling and labelled to reveal the artist’s non-deluxe raw materials: "tinfoil" and "plastic shells" and the like. One storage box was marked "Caravaggio, etc", hinting at Cornell’s belief that 17th-century Italian painters are no more precious than the vast et cetera that is day-to-day life.

During his lifetime, Cornell’s eccentric habits did not exactly serve to burnish his artistic reputation. In the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, critics dismissed his boxes as "toys for adults", a category near the bottom of established art-world hierarchies. Cornell had to wait for the advent of Pop Art in the 1960s, which returned realism and still-life to avant-garde art, before his achievement was fully recognised; he was given a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1967. Today, in a dramatic reversal, installation and assemblage are ubiquitous; they can seem like the default media for a generation of artists intent on lending their work a caffeinated hit of real life. Cornell’s work has never been more relevant than it is right now.

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust, curated by Sarah Lea at the RA and Jasper Sharp at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna – to which it travels in the autumn – is, astoundingly, the first museum show of Cornell’s work to be held in England since 1981, and the first ever in Austria. It promises to be an exhibition of exceptional lucidity and coherence, with 80-odd works in various media that share the theme of imaginary travel. In addition to the glass-fronted shadow boxes for which the artist is best known (see below), the show will also include over 20 collages; enigmatic objets small enough to fit in your palm; and three of Cornell’s experimental films, including the ingenious collage films that were spliced together by the artist from found commercial footage.

His talent lay in alchemising commonly discarded objects into a visually compelling state of being.

Cornell was a relative latecomer to art. Born in Nyack, New York, in 1903, the oldest of four siblings, he was 13 years old when his father’s untimely death saddled him with adult responsibilities. After completing high school, he was obliged to support his mother and siblings and took a job as a textile salesman. Already he was collecting memorabilia on his rounds through lower Manhattan. He started making art after his visits to galleries acquainted him with a new medium – collage. This was around 1931, before he had set up his studio. In the quiet hours after his family had gone to sleep, he would sit at the kitchen table with his scissors and his glue pot and an array of old illustrated books.

Cornell’s approach to art might seem to echo, at least partly, the mission of the Royal Academy and Burlington House’s other learned societies, whose existence owes something to the Enlightenment belief that human knowledge can be collected and classified. Cornell, of course, was a collector by temperament, and his boxes represent the systematising of his objects. Indeed, he openly celebrated his curating passions in his so-called series of "Museum" boxes from the late 1940s. Cornell generally worked in series, and Museum (1949), in the RA show, is a wonderfully strange object that at first glance looks like an ordinary wooden box – perhaps for jewellery – with a hinged lid and a keyhole. Inside, 20 little bundles of what appear to be rolled-up strips of text printed in French are arranged in four neat rows. Each little bundle is in fact a container for tiny shells and trinkets and produces intriguing sounds when shaken.

Untitled (Pinturicchio Boy), 1942-52

Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery, 1943

Pharmacy, 1943

Untitled (M’lle Faretti), 1933

The piece reminds us that Cornell expressed the most baffling fantasies with precisely calibrated arrangements of objects. Moreover, he was not collecting what are usually defined as collectibles – objects distinguished by their beauty or rarity or historical importance. Rather, he attached the highest value to objects of little or no intrinsic worth. I emphasise his inexpensive materials because a cursory glance at Cornell’s boxes could lead you to think that he was constructing reliquaries for coveted possessions, when in fact his talent lay in alchemising commonly discarded objects into a visually compelling state of being.

Some of his boxes are less cryptic, and more naturalistic, such as Untitled (Owl Habitat), from the 1940s. The snowy owl trapped behind a pane of glass is not a fancy piece of taxidermy fit for a natural history diorama, but a mere paper illustration pasted onto plywood. The midnight-blue forest the owl inhabits is contrived from painted bark and lichen. Cornell, of course, was himself a famous night owl. In some ways the owl box can seem as close as he ever came to self-portraiture, with its majestic creature alone in the woods, eyes wide, watching.

The box, by the way, happens to have a distinguished provenance. I first stumbled upon it last summer when I visited the artist Jasper Johns Hon RA in his studio in North- west Connecticut. The box, he explained, was a birthday gift from Leo Castelli, who was his art dealer, and who perhaps recognised affinities between the work of Cornell and the much younger Johns: the appropriation of common objects, the melancholy symbolism.

For all his love of classification, Cornell refused to classify himself. He did not see himself as part of any movement, and resisted attempts to link him to various French -isms. Some see him as a belated Symbolist poet, who inherited from Stéphane Mallarmé a devotion to fragmentary forms and veiled meanings. Some view him as a Dadaist, and it is true that he befriended Duchamp in the 1930s and shared his affection for the found object. Others point out that Cornell’s primary technique – the juxtaposition of unrelated images and objects – was adopted from orthodox Surrealist practice and obliges him to be remembered as an American Surrealist. Cornell himself rejected the appellation and noted, "I do not share in the subconscious and the dream theories of the Surrealists."

Las Meninas (2Xist), 2013

Monogram, 1955-59

A Parrot for Juan Gris, 1953-54

Untitled (Owl Habitat), c. mid- to late 1940s

My own feeling is that Cornell is best described as the eminence grise of assemblage – he laid the groundwork for the coming mash-up in late 20th-century art. Too much attention has been lavished on the Francophile in Cornell and not enough has been said about his American qualities. He belongs to the vein of American realism that elevated prosaic objects to art, going back to John F. Peto’s trompe l’oeil paintings in the late 19th century and extending up through Warhol’s soup cans and Jeff Koons Hon RA’s 8ft-tall aluminium lobsters. (Art, I realise, is not a race between two contestants, but Cornell arranged plastic lobsters into fantasy ballets decades before Koons revealed a fascination with marine crustacea.)

Cornell is seldom given his due in art-history textbooks, which tend to repeat the familiar post- war narrative in which Robert Rauschenberg and his ‘Combines’ (Monogram, 1955-59) launched the junk-into-art aesthetic in America. (Put another way, Rauschenberg did for New York what Peter Blake did for London.) Yet Cornell directly inspired Rauschenberg’s early use of found objects. They befriended each other around 1953, when Rauschenberg, then an unknown artist in his twenties, was making "hanging fetishes" and elemental sculptures notable for their accretions of recycled detritus. "The only difference between me and Cornell," Rauschenberg once told me, "is that he put his work behind glass, and mine is out in the world."

What debt do today’s recyclers owe to Cornell? On any day, making the rounds of the galleries in New York, you might be stopped in your tracks by an exquisite construction cobbled together by Rachel Harrison, Isa Genzken or Jessica Stockholder, or the sparer, almost fragile cardboard-and-tape creations of Gedi Sibony, or the socially charged bric- a-brac assembled by Nick Cave. You can even speak of an entire subcategory of artists who put stuff into glass vitrines — Damien Hirst, Mark Dion, David Altmejd and Josephine Meckseper (Las Meninas (2Xist), 2013, above) come to mind.

Of course, their work might not seem particularly Cornellian. He worked on an intimate scale, in contrast to the expensively fabricated, elephantine assemblages to be seen in so many galleries today. Interestingly, the found object – deployed by Cornell as a talisman of the past and transfigured so successfully that a dimestore trinket can seem antique – has evolved to become, in contemporary art, an extension of our round-the-clock consumerist present and a critique of the global economy.

At any rate, as Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust descends on London and then Vienna, one is reminded that the artist’s work is infinitely better travelled than he was. He loved Europe, so long as he kept a protective distance from it and could create a space large enough in which to dream. He was very much a poet of yearning who seemed to believe that true love is unrequited. Nonetheless, I think we can safely say that if London or Vienna does decide to love him back, that will not ruin the relationship.

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust is in The Sackler Wing at the RA from 4 July — 27 September 2015.

Deborah Solomon is the art critic of WNYC Public Radio in New York. Her most recent book is American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell. Her Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell (1997) will be republished this autumn in a new edition by Other Press, New York.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Five Brazilian cultural icons from the 20th century

28 February 2025

A love letter to the gallery gift shop

18 November 2024

Painting the town: Florence in 1504

15 November 2024

Moving a masterpiece

7 November 2024

In memoriam: Norman Ackroyd RA

20 September 2024