Watch these spaces: the future of art schools

By Anna Coatman

Published on 18 March 2016

As Britain’s art schools experience an era of radical change, what do students stand to gain and lose? Anna Coatman explores the past, present and future of art education.

From the Spring 2016 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

As night fell on 14 December 2015, the lights at the art school came on. If you happened to walk by, you’ll have seen the silhouettes of over 100 students appear, some waving, some with hands on hips, framed by the brightly-lit grid of windows. This was more than just an art project – it was a visual protest. The students pressed against the glass wanted to make their presence felt; they were occupying the £50 million building in Aldgate in an attempt to halt London Metropolitan University’s plans to sell it off to property developers.

If these plans go ahead, the Sir John Cass Faculty of Art, Architecture and Design will be relocated to Holloway, joining the main campus of its parent institution. The sale will provide much-needed funds for the university. But campaigners are concerned that it will also mean less studio space, fewer courses and less creative autonomy for the Cass, pointing out that – among other benefits – the architecture of the school’s current home encourages students from different disciplines to share ideas and collaborate.

Concerns were also aired when Central Saint Martins announced that it was relocating to a state-of-the-art, converted granary depot in King’s Cross, which opened in 2011. For a while after the students had left its historic Lethaby building in Holborn, mournful slogans – "R.I.P." – were still daubed on the walls and windows. Though the Lethaby had many problems, including severe leaks, some were sad to see it go, fearing they might lose the unique kind of education once offered within it.

Art School 37, 2013

From Paul Winstanley’s series of paintings ‘Art School’, which documents art school studio spaces empty between school years

Art School 35, 2013

From Paul Winstanley’s series of paintings ‘Art School’, which documents art school studio spaces empty between school years

Another London art school, the Royal Academy Schools, is unusual in being independent and charitably funded, and therefore sheltered from pressures to expand or move. It is not immune, however, from change. The institution is planning to restore and modernise its 19th-century building on the Royal Academy of Arts site in Mayfair, to mark its 250th anniversary in 2019. These plans coincide with a larger redevelopment project at the RA by David Chipperfield Architects. But they are also about creating work spaces suitable for the 21st century.

Change is in the air, prompting questions about what art schools are for, what they will look like in the future – and what they were like in the past. Looking beyond the campaigns and heated commentary surrounding the relocations of the Cass and Central Saint Martins – not to mention the earlier move of Chelsea School of Art in 2005, and the restoration of the Glasgow School of Art after a fire in 2014 – to a recent plethora of talks and books on the history of art schools, nostalgia for what has gone is the keynote. So what is it, exactly, that we have lost, or stand to lose? Should we feel positive about leaving any of it behind? And what do we stand to gain in its place?

The foundations of art schools as we now know them were laid in the 1960s, when many small, local colleges merged to create tertiary- level polytechnics. Students were treated more like independent artists rather than pupils learning a craft. Here they could study for a Diploma in Art and Design, an innovative qualification developed by painter William Coldstream, the Head of the National Advisory Council on Art Education.

Marking a shift away from purely practical studies, the DipAD included an art history element, and encouraged more experimentation across different media. Coldstream also introduced a crucial ‘let-out clause’ that allowed students who showed exceptional artistic promise, yet who did not have the required educational qualifications, to be admitted into art schools. Art school became a haven for a small number of lucky school-leavers who hadn’t fitted comfortably within the conventional academic system.

These new art schools were shaped by the cultural climate of the time, which in many ways couldn’t be more different to our own. In his most recent Spending Review, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Obsorne announced that Arts Council England would receive a small increase in funding (in cash terms), yet its budget had already been slashed by 36 per cent between 2010 and 2015. On top of this, austerity cuts to councils mean that local arts funding often loses out when pitted against other essential services. In contrast, the 1960s saw unprecedented growth in investment in arts and humanities.

The pioneering Labour Arts Minister Jennie Lee set the tone in 1965, when she produced the only government White Paper on the arts there has ever been (51 years on, minister for culture Ed Vaizey is about to produce the second such White Paper – it will be interesting to see how it compares). Buoyed by a post-war spirit of optimism and altruism that had made the development of the modern welfare state possible (incidentally, Lee was married to Nye Bevan, the Labour Minister who spearheaded the creation of the NHS), Lee declared: "[in] any civilised community the arts and associated amenities... must occupy a central place. Their enjoyment should not be regarded as something remote from everyday life." This seminal document described the key role that the arts play in a healthy society, stressing that they should be accessible to people of all classes, up and down the country.

This positivity went hand in hand with widespread political upheaval. Now-legendary protests were sweeping the world in 1968, and at Hornsey Art College students staged a six-week sit-in as a response to the withdrawal of Student Union funds, among other grievances. Over ten days, they took charge of the administration of the college, and called for a review of the curriculum. Other art schools across the country soon swelled the wave of protests. The 2015 occupation of the Cass – and a similar sit-in that took place at Central Saint Martins earlier that year – recalls this rebellious, bygone era. A number of the artists who came through the new polytechnics of the 1960s and ’70s would go on to teach in the institutions that rose to prominence in the 1980s, such as Goldsmiths College, where the emphasis was on Conceptualism, theory and experimentation. Michael Craig-Martin RA, who taught at Goldsmiths, wrote in his recent book On Being An Artist, "Goldsmiths was the first art school I knew that was clearly the product of my own generation... All of the traditional attitudes, procedures and structures that were taken for granted in most art schools were questioned and, if found irrelevant, abandoned."

Art School 14, 2013

From Paul Winstanley’s series of paintings ‘Art School’, which documents art school studio spaces empty between school years

Art School 4, 2013

From Paul Winstanley’s series of paintings ‘Art School’, which documents art school studio spaces empty between school years

The idea that the 1960s, the ’70s and, to a lesser extent, the ’80s represent a "golden age" for art schools is seductive, and it is easy to see why it is gaining traction. But it is important to understand that there is a mythic element to it. As with any dominant narrative, it is safe to assume that there are other, dissenting voices that have not been heard. For instance, today, course sizes are much larger than they used to be – meaning that one-to-one tuition and large studio spaces are virtually things of the past. Yet these things were only possible in the first place because just 5 per cent of young people went on to higher education in the 1960s, as compared to the 45 per cent who do so now. And though grants, in theory, enabled young people from working class backgrounds to go to art school, the demographic of these institutions was even then, in reality, predominantly middle/upper class.

The flipside of those days of unlimited freedom of expression was a lack of guidance and support. The ‘anything-goes’ teaching style that characterised the ‘golden age’ did not suit everyone, leaving some adrift. Last, but certainly not least, arts faculties were held much less accountable for their actions than they are in 2016 and – going by first-hand accounts – were by no means free from institutional sexism, male chauvinism and casual misogyny.

Things have changed a lot in the past 50 years socially and politically, and art schools have adapted accordingly. A significant shift came in 1992, when John Major’s Conservative government passed the Further and Higher Education Act, allowing polytechnics to become universities. While some art schools, such as Leeds College of Art, the Royal College of Art and Glasgow School of Art, remain independent, most now belong to larger universities – and have thus been grappling with the same issues that those universities have had to face ever since.

For instance, government teaching grants for arts and humanities courses were withdrawn between 2010 and 2014, meaning that many art schools and faculties faced serious financial challenges. Art courses are now largely funded by fees, and art students – like all university students – can now expect to pay up to £9,000 a year. The fear of leaving with huge debt and uncertain career prospects makes the decision about whether to go to art school high risk. At the same time, if you want to work in the creative industries, the competitive job market means that graduating – ideally from "a good place" – is more important than ever.

Yet in terms of future generations, aspiring young artists – particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds – face greater obstacles before they get to art school, as well as when they leave. In primary schools, especially those with poorer catchment areas, there’s a risk that time spent studying the ‘key’ subjects of English, Maths and Science could overtake other subjects, including Art. In secondary schools, plans to roll out the new EBacc qualification could mean that virtually every 16-year-old would have to study for GCSEs in English Literature and English Language, Maths, double or triple Science, a modern and/or ancient language, History and/or Geography. As pupils take, on average, eight GCSEs, this means that Art, Dance, Design, Drama, Music and other subjects relevant to the creative industries will likely be squeezed out. Realising this, more than 23,000 individuals and 160 organisations – including the Royal Academy of Arts – have supported the campaign against the proposals.

Meanwhile, sixth-form colleges are feeling the strain of local government cuts, and arts courses have often been the first to suffer. Hackney College, for instance, last year axed three arts courses, including the Foundation Diploma – a pre-requisite qualification for those applying to study fine art degree courses.

As Neil Griffiths, the co-founder of Arts Emergency (a charity that aims to tackle social inequality in the arts) explains, "there is a real risk that art could become a luxury subject accessible only to the privileged." Bob and Roberta Smith RA – a tutor at the Cass and a leading campaigner to save it – agrees, cautioning, "we are really heading back now, not to the 1960s, but to the ’30s, when art schools were only for the elite."

For those young people who do get to go, art school is no guarantee of a career as an artist. Ironically, though there is more money than ever before to be made as a successful artist, it is also much harder for recent graduates to survive – thanks to soaring rents and the shrinking of benefits support and funding.

It has always been difficult to make a living as an artist, meaning that it has always been more risky for the underprivileged than the privileged. But the safety nets that were in place in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s have been whipped away. The days of developing art while eking out an existence on the dole in cheap rented accommodation are gone; it is now practically impossible to live in London and make a living as an up-and-coming artist without the financial support of a wealthy family behind you.

All of this brings to mind the 1995 Pulp single Common People, about a rich girl from Greece who studies sculpture at St Martins College, and wants to be one of the "common people", but calls her dad to "stop it all" when reality starts to bite. The song charmingly skewers the notion that art schools are little utopias, where all are equal. Many art schools, however, are doing their best to prepare students for the tough world beyond their walls – including Central Saint Martins. Here students are encouraged to develop practices that will be sustainable after they graduate.

As Alex Schady, leader of its fine art programme, explains, "We have to think creatively about how we are preparing our students for the world beyond. It is not appropriate to prepare them by giving them the most enormous studio and no financial worries and endless one-to-one tutorials, because what they are facing when they leave here, especially if they are staying in London, is having a peripatetic studio, if a studio at all, and having to develop elastic practices that can work alongside having to have a job, and showing work erratically."

The new campus plays an important role in shaping these "elastic" practices, with its impressive, large-scale, temporary exhibition spaces, available to students on a rotating basis, and its open, communal areas. As Mick Finch, course leader of the BA in Fine Art, enthuses, "The thing we love about this place is that it’s open, it’s public, we actually meet people from other courses. It’s a fabulous collaborative environment, a really lovely place to work."

While it is undoubtedly true that art students need to be as well-equipped as possible for the tricky contemporary art world they are about to be thrust into, having the time, space and financial freedom to develop as an artist has its own inherent value. Seventeen very fortunate artists are given that chance each year at the RA Schools, embarking on the country’s only three- year, entirely fee-free postgraduate programme.

The RA Schools, founded in 1769, is the longest established art school in Britain. In the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, the RA Schools had a reputation for being conservative, valuing traditional skills such as life drawing – the antithesis of the more progressive art schools of the "golden age". But in 1998 the programme was transformed into a contemporary course, similar to the best offered elsewhere at the time. Today, with Eileen Cooper RA as the Schools' Keeper (the Academician responsible for the art school), the emphasis is still on creating forward-looking work – just as it is at most art schools across Britain. But it is now one of the few places where students can develop their ideas in an environment similar, in some key respects, to that associated with the "golden age" of art schools.

In addition to removing the fear of debt, and providing a generous amount of personalised tuition, one unique thing that the RA Schools programme offers is time. Most art schools offer one-year masters courses and, as Eliza Bonham Carter, Curator and Head of the Schools explains, "the best thing that happens on a one-year MA is that your brain is totally blown apart by new thinking and new ideas. But you don’t have time then to really act on those, whereas a three-year programme allows you to do that, embedding those ideas into your practice."

Another thing is space. The RA Schools was designed in 1868 by an alumnus, Sydney Smirke RA, and later extended by Norman Shaw RA between 1881 and 1885. The fact that the building was created by a student for students is, Bonham Carter believes, the key to its enduring success: "Apart from the fact the roof leaks and that there are big radiators on all the walls, it’s perfect.

"The light is fantastic and it’s all on one floor, which is delightful because it means everyone is in the same place. And because each studio has two doors you can move through the school in a very open way, without interrupting anyone. It’s really interesting to think about how much all of that informs the work that happens here." In his plans to modernise the Schools David Chipperfield RA intends to work with Smirke’s original floor plan, removing the temporary walls and features that were installed subsequently and building new, up-to-date workshops suitable for contemporary art practices.

The RA Schools is funded by individual patrons, companies and trusts and foundations, plus an annual Schools Auction and some of the proceeds from the Summer Exhibition, as well as being supported by Newton Investment Management. Thus cushioned from the financial pressures that other art schools have to contend with, the RA Schools is a sanctuary for those lucky enough to attend (as well as being a prestigious addition to their CVs). But the obvious downside to the Academy’s model is that so few students can benefit.

The RA Schools is not the only place that offers an alternative to most art schools. In response to high fees, commercialisation and rigid assessment criteria, independent, guerrilla-style art schools are starting to pop up. One notable example is Open School East. Based in a former library and community centre in De Beauvoir Town, east London, the school offers a free, experimental, collaborative study programme for emerging artists, as well as events and activities open to the local community. Funding comes from trusts, foundations, individuals and art galleries, as well as Arts Council England.

‘Associates’ at the school come together for two days a week to meet mentors and work together on projects. The emphasis is on supported, self-led development, rather than tuition as such. As with the RA Schools, the programme is non-accredited, and some seminars and workshops and presentations are open to the public.

John Lawrence was an associate at Open School East in 2015 and found the experience liberating. "It was great to work in a truly collaborative fashion, and to have real agency in providing cultural activity at the highest level to local audiences and the London community. A DIY ethos requires a lot of energy from all involved, but it also allows for the possibility to engage and react to things on the fly." While initiatives like this are exciting, it is unlikely that they can or will usurp mainstream art schools – nor is this something we should hope for.

As Lawrence admits, "Ideally, alternative art school models wouldn’t need to exist. Really, they are papering over the cracks that some mainstream education models overlook and providing free education at a time when £9,000 in tuition fees simply isn’t a viable option for many." Griffiths agrees: "Art schools and universities are hundreds of years old and they’ve got great value as they are – we should fight to defend them, not just create alternatives."

The campaign to reform the EBacc is supported by the Royal Academy; visit www.baccforthefuture.com

Paul Winstanley, Art School: New Prints and Panel Paintings Alan Cristea Gallery, 17 March–7 May 2016.

Anna Coatman (@AnnaCoatman) is Assistant Editor of RA Magazine.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

3 young artists on getting into the Young Artists' Summer Show

18 September 2020

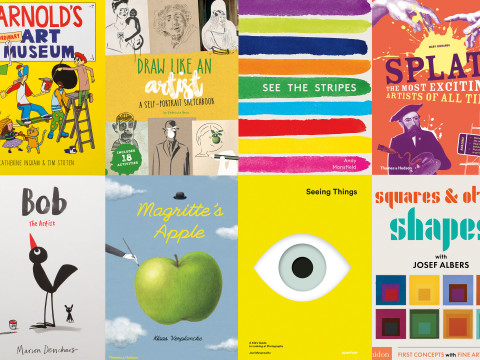

The best art books for kids

2 December 2016

Going for gold: Venice in the 16th century

7 March 2016

The enigma of Giorgione

7 March 2016