Eight mind-blowing graphic novels for beginners

By Rachel Cooke

Published on 5 September 2018

As Observer journalist and critic Rachel Cooke champions the art of the graphic novel at the RA's Festival of Ideas, she tells us why we're in a golden age for the comic – and offers up eight greats to get you started.

Where to start with comics? People come to them, after all, with so many preconceptions. They’re childish. They’re all sci-fi and superheroes. Their most devoted readers are (as the Iranian cartoonist, Marjane Satrapi, once put it) blokes with pot-bellies, pimples and ponytails. But this is all wrong, of course. Comics – graphic novels, if you want to use the modish term – can do everything regular books can, with the added bonus that they provide a feast for the eye and take so vastly less time to read. (And they are both written, and read, by as many women as men.)

This is, moreover, something of a golden age for the comic. When I first began reviewing them regularly, more than 10 years ago, I used to worry there would not be enough of sufficient quality to keep me supplied. These days, though, my beauties are too many, not too few. What follows is a list that comprises some of my favourites. It isn’t intended to be exhaustive, or even remotely scientific, but every one of these books is truly great, and should instil in anyone who picks them up a powerful desire to find more just like it.

1. Jerusalem: Chronicles From The Holy City, Guy Delisle

(Jonathan Cape, Vintage)

Guy Delisle is a French comics writer whose travel journals – Shenzhen, Pyongyang, Burma Chronicles – document his journeys so vividly you return to your regular guidebook with a heavy heart. As he has put it: “My books are always at pavement level. That’s what I do.” Jerusalem, an account of the year he and his wife, Nadege, an administrator with Médicins Sans Frontières, spent living in the city, was published in 2012, the same year it won the main prize at the Angoulême International Comics festival, and it is a minor miracle: concise, even-handed, singular in its observations. Also, beautifully drawn. In its pages, you will certainly find the settlements and the security wall. But you will also, among many other things, witness the one night of the year when the Haredim get paralytically drunk, and meet the priest who keeps a collection of horror films at his church on the Mount of Olives. Fascinating and enlightening.

2. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Roz Chast

(Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.)

Roz Chast is a New Yorker cartoonist who can make pretty much anything hilarious. But with her 2014 memoir of decrepitude – specifically, the decrepitude of her ageing parents, marooned in their crumbling apartment in deepest Brooklyn – she surpassed even herself, producing what is surely one of the most blackly funny comics ever written. Chast is her parents’ only child, and she takes up their story – born in 1912, they have at this point been married for 63 years – in 2001, just as their isolation starts to become a serious problem (George is a phobic who is scared of everyone and everything; Elizabeth is a harridan who takes some pleasure in giving people “a blast from Chast”; between them, they have no friends, and few relatives). Though she dreads visiting their home, a grimy hoarder’s paradise, it is perfect fodder for her sweet-sour wit – and as she chronicles their increasingly difficult last years, she is always careful to be every bit as hard on herself as she is on them.

Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City, 2012

Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir, 2014

Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, 2003/4

Black Hole, 2004

3. Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

(Jonathan Cape, Vintage)

Lots of people know Persepolis as an Oscar-nominated animated film, but it was a comic first of all, published in two parts in 2003 and 2004. Satrapi, the daughter of Iranian Marxists, grew up in Tehran, where she witnessed both the Islamic Revolution and the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War; later, she left for Europe, where she still lives. Persepolis, a memoir in which she sets her own story against the backdrop of these momentous events in the country of her birth, has an outward simplicity that utterly beguiles: her black and white drawings resemble old-fashioned woodcuts; her narrative is almost breezily concise. But do not be deceived. I have learned as much about Iran from Satrapi (her later books include Embroideries and Chicken With Plums) as by reading any journalist or historian, the great Ryszard Kapuscinksi included.

4. Black Hole, Charles Burns

(Jonathan Cape, Vintage)

Burns’s Black Hole, published in 2004, is now considered a bona fide classic. Go back to it, though, and it feels as fresh as ever: not only a page-turner, but a dystopian fable whose message seems to grow ever more powerful down the years. Based on his childhood in 1970s Seattle, the novel is about a group of high school students who catch a sexually transmitted disease that leaves them with some highly alarming side effects. Burns isn’t interested in the origins of this plague, nor in how it might be cured; rather, his attention is on how it changes the attitude of these teenagers both to their bodies, and to each other. Black Hole, stunningly executed in monochrome, carries with it a whiff of the horror flick or the B-movie. But its characters are never less than utterly believable and sympathetic: vulnerable kids who are at the mercy of peer pressure and their hormones, and who long only to escape the claustrophobia of home. Gripping, and enduringly true.

More at the Festival of Ideas

Join a sparkling line-up of speakers from across the arts, as the RA hosts a meeting of great minds in art, architecture, literature, design, dance, film and music. Be part of the most thought-provoking conversations in London in these ten days of electric debate, discussion and workshops.

5. Driving Short Distances, Joff Winterhart

(Jonathan Cape, Vintage)

Winterhart’s second graphic novel follows 27-year-old Sam as he returns to the boring British town where he grew up, following three failed attempts at university, and a breakdown. There, he gets a boring job, working with a man called Keith Nutt whose business involves filters, Portakabins and spending large amounts of time in his Audi eating pasties. Nutt, with his hairy nostrils and his sausage fingers, is something of a pathetic figure: a little bit Alan Partridge, a little bit David Brent. But his effect on Sam is remarkable. The more time the two men spend together, the stronger Sam grows – and meanwhile, Keith, seems visibly to shrink, his loneliness becoming ever more apparent to the protege he is so determined to patronise. An exquisitely rendered tale of masculinity and urban isolation, lots of people, Zadie Smith among them, regard Driving Short Distances as a masterpiece – and once you’ve read it, it’s almost impossible to disagree.

6. Maus, Art Spiegelman

(Penguin)

Recommending Maus feels rather predictable, but then again, no starter list of graphic novels would be complete without it, for this book, the first volume of which was published in 1989 (Volume 2 followed five years later), permanently changed the way many people – most notably, perhaps, literary publishers – thought about comics. In essence, it tells the story of its author’s father, Vladek, a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor, with whom his son had a somewhat troubled relationship. Spiegelman’s masterstroke, however, is to deploy animals rather than people in his narrative: his Jews are depicted as mice, his Nazis as cats, and his Poles as pigs. This isn’t sentimental. One of the sources of Maus’s immense power lies in Spiegelman’s refusal to sanctify the survivor. During the war, Vladek lost his six-year-old son, Richieu, poisoned by the aunt in order that he might avoid the gas chambers; most of his extended family died, and he endured months of the most appalling fear and hardship in Auschwitz-Birkenau and, later, Dachau. But such suffering, Spiegelman wants us to understand, doesn't make a person better; it only makes them suffer.

Driving Short Distances, 2017

Maus, 1989

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, 2006

The Arab of the Future, 2014

7. Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

(Jonathan Cape, Vintage)

The graphic memoir (and now Tony-award winning Broadway musical) that first turned me fully onto comics, Bechdel’s 2006 account of her childhood in Beech Creek, Pennsylvania, still stands head and shoulders above many similar books in terms of the richness of its themes (sexuality, suicide, the complexity of family life). Bechdel’s father, Bruce, ran a funeral home – the “fun home” of the book’s title – but his real passion was the restoration of the family’s Victorian house, a project that consumed him, much to the bafflement of his daughter. Why was he so obsessed with period details? And what was the connection between this and his periodic moods and bouts of rage? I will not give the game away here, but suffice to say that Bechdel, having come to terms with her own sexuality, comes to realise that she and her father have more in common than she ever realised. Bulging with literary allusions from Proust to Scott Fitzgerald, Fun Home is a book that demands to be read again and again.

8. The Arab of the Future, Riad Sattouf

(Metropolitan Books)

So far, two volumes of Riad Sattouf’s brilliant extended memoir, originally published in French, are available in English (the third comes out in the UK in November). Sattouf, a former cartoonist at Charlie Hebdo, has a French mother and a father who came originally from Homs in Syria (the couple met in Paris, when they were students), and in The Arab of the Future he sets out to tell the story of his confusing childhood, lived between the two countries. These books are extremely intimate – the boy Riad observes at unnervingly close quarters his parents’ increasingly fractious marriage – but they also throw some light on the origins of both the war in Syria, and the revolution in Libya, where Sattouf’s academic father teaches for a while. Funny, pert and daring, Sattouf goes places few writers dare visit, with ever richer results – and what huge characters he gives us, not least his blustering, boastful father Abdel-Razak, a man whose qualities feel at times to be distinctly Dickensian.

Rachel Cooke is a critic and journalist at the Observer.

Related articles

10 novels about art you won't put down

10 June 2022

Four art biographies to read this autumn

11 September 2017

The artists behind your favourite childhood books

25 August 2017

The best art books for foodies

28 February 2017

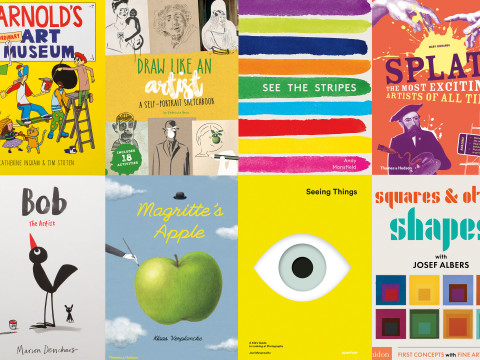

The best art books for kids

2 December 2016