Novelist Tessa Hadley on the intriguing world of Félix Vallotton

By Tessa Hadley

Published on 23 June 2019

With their secret trysts and satirical twists, the paintings and prints of the Paris-based Swiss artist Félix Vallotton prompt more questions than answers. Novelist Tessa Hadley gives her personal response to the artist’s enigmatic world.

From the Summer 2019 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Here is something I’ve never seen painted before, and yet I feel I know the subject intimately; it’s familiar from daily life. A woman crouches in front of a linen cupboard, searching for something. It’s dark, so she has put down a lamp on the floor beside her. Light from the oil lamp makes the piles of white linen glow against the darkness of the further interior and throws confusing shadows backwards from the open cupboard doors, so that the space seems like a cave opened up in the night, mysterious and ambiguous, a revelation whose dimensions at first we cannot quite understand.

This is a bourgeois household: there’s plenty of linen, beautifully laundered and folded and sorted. Is the woman who crouches before it the mistress, or the maid? The mistress of this cupboard surely doesn’t make up her own beds, or set her own table. She might, however, keep its contents carefully supervised; her linens might still carry old dowry-overtones and help to constitute her woman’s identity. She’s seen in silhouette, and from behind; something about how she crouches there, balancing herself on one hand, looks assertive, like a mistress surveying her domain, not routine like a maid accomplishing her work. And actually she hasn’t positioned herself so as to pull out anything from among the piles of sheets and tablecloths. She’s puzzling over the space below the bottom shelf, as if there’s something stored there – in the box we can just make out – that she has just remembered, or unexpectedly wanted.

Woman Searching Through a Cupboard is a marvellous painting, I think, startling and moving, wholly original. Would we know, if we knew nothing else about it, whether it was painted by a man or a woman? We could guess that it comes from around the late 19th or early 20th century (1901, as it happens). And in fact the artist was a man: Félix Vallotton, the subject of a new exhibition at the RA. Vallotton came from Lausanne but made his career as a painter and illustrator and woodcut artist in Paris; he was associated with the Nabis group alongside Vuillard and Bonnard but his work doesn’t look very much like theirs. The more Parisian he gets, the more his art is haunted by something else: something Protestant and Northern European, cool and with a whiff of neurasthenia, mental rather than sensual. For me he’s a thrilling new discovery.

Perhaps we’d guess, even if we didn’t know, that a man painted this cupboard, a man not wholly in love with linen cupboards or with women, with the way bourgeois women lived in 1900, the way they were. Vallotton makes the scene somehow alien, not familiar: he un-domesticates it. The woman has her back turned and appears unaware of our looking at her, or indifferent to it. The painter has caught her alone, when she’s not arranged for a male audience to admire, not concerned to appeal – though she’s not ashamed either, of having her well-ordered full cupboard seen. He has chosen to represent her in a private moment, as painters love to do with women: what’s unusual is that the moment isn’t of dreamy introspection and absence (like Chardin’s wife drinking tea, say) but of forceful authority and possession. I think the revelation of the cupboard’s interior, its forbidding gates flung open, the woman crouched over her mysteries like a priestess, makes Vallotton uneasy even as it fascinates him. The interior glows with its own light, like a sacred space, but that’s as much in irony as in celebration. The painting is wary in relation to the sheer complexity of this bourgeois domestic order, the work it takes, that female mental work which might seem to an intelligent man, and especially to an artist, so numbingly materialistic, futile in its repetitions.

Vallotton in his youth was anti-bourgeois, as was de rigueur for any artist in Paris; he made his name at first through his satirical woodcuts and illustrations, wrote and illustrated for the radical papers, and lived in the Latin Quarter with a seamstress, Hélène Châtenay. In 1899 however, aged 33, he left Hélène to marry Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, a wealthy Jewish widow with three children who happened also to be the sister of important art dealers. Vallotton’s bohemian friends may have disapproved, but the uneasy interiors Vallotton painted in the first years of this marriage seem to me to be among his best works, and just because of the unease. He’s tenderly attentive in them to his wife, and not hostile to his new bourgeois milieu exactly – but not comfortably at home either. He admires the Bernheim men, his in-laws, transacting business in their office or at play; they exude sophistication and assurance. But Vallotton depicts them from across great expanses of desk or billiard table, as if he can’t imagine getting any nearer, belonging inside their intimate circle. “I live among strangers,” he wrote in a letter.

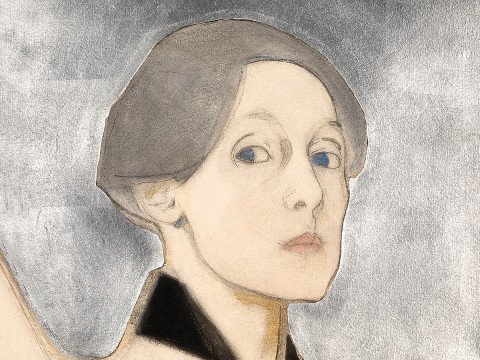

This might have half-suited him; in his self-portrait, from 1897, he doesn’t look like a man eager to move in with a crowd of friends. How delicately Northern European the self-scrutiny in this portrait feels, and not only because of the austere painterly realism, no hint of an impressionistic brushstroke. This man might be a sensualist – smudged eyes, shapely wide satyr’s face – but he’s not sensual. He’s fastidious, disenchanted; his good looks are a fortress, not an opportunity, they’re part of his self-possession. Such a man, holding himself back from belonging, might make good art out of the opulent interiors of strangers, alien to his own taste. His pictures of Gabrielle at home are crowded with the clashing colours and patterns of clothes and wallpaper, upholstery and rugs: red walls, gilt clock, striped gold-and-pink wallpaper, fringed dresses, ornaments, flowers, tiled fireplace, parquet floor. The effect is overwhelming, luxuriant: a look no doubt associated with the new flood of consumer goods and shops to buy them in (Vallotton in his woodcuts satirised Le Bon Marché, the famous Paris department store). And what might have been cloying as interior decor becomes exotic, striking, unsettling, when it’s rendered in paint with Vallotton’s almost anthropological coolness (anthropological like Gauguin in Tahiti).

The Red Room, Etretat (La Chambre rouge, Etretat), 1899

Interior with Woman in Red (Intérieur avec femme en rouge de dos), 1903

The Theatre Box (La Loge de Théâtre, le monsieur et la dame), 1909

The Ball (Le Ballon), 1899

In Interior with Woman in Red from 1903, rooms open theatrically into other rooms and yet further rooms; Gabrielle presides in the middle distance with her back to us. We see just as if it were a stage set how the drapes have been tacked to the walls, and how someone decided to paint the risers on the steps to match the doors; the colours – blue, crimson, orange, pale green – don’t merge seductively but startle in juxtaposition. In an innermost chamber there’s a marital bed, but although the painting is windowless it’s full of daylight. Gabrielle is in her dressing gown, but she’s on her way to getting dressed, not undressed – yet this stolen glimpse of a household busy with its routine feels mysterious and excluding as any erotic fantasy. In The Red Room, Etretat (1899), Gabrielle sits calmly in a chair, while her baby niece on the floor absorbedly and deliberately tears up a piece of paper. Is Vallotton perturbed by how his wife is smiling and fatalistic, overseeing the destruction of something so closely resembling his own work?

His subjects are often these accidental comedies of domesticity. We mustn’t mistake that coolly Protestant self-scrutiny in the self-portrait for solemnity; it would be missing the key to his work if we didn’t realise that he sees things are funny, in their oddity and unexpectedness. That’s the habit of perception he deployed hundreds of times when he was first managing to earn a living from art, making illustrations for magazines out of the subjects he found around him every day – buying a hat, wielding an umbrella into wind and rain, watching fireworks, protesting in a crowd, playing the piano so feelingly that the tulips on the wallpaper droop in sympathy. There’s a police charge and an execution too, yet even these are half-comically absurd.

When Vallotton turns to painting, he conceives his subjects as ambitiously as anyone. Yet he can’t quite ever lose – it’s in his practice or it’s in his nature – that satirical habit of perception, catching the quirky oddity of what people do, transforming it into the wit of shape and style. Some of his most exciting paintings have the same gestural minimalism as his illustrations: The Theatre Box (1909), for example, where a couple are all but concealed from us by the low wall of their box, everything centring on the white knot of her gloved hand. Or in The Ball (1899), a playing child seen from above, a schematic outline against a simplified landscape, creates a thrilling vertiginous space of freedom. In other paintings the strong design pushes too explicitly towards a point, or a joke. And maybe it’s his inveterate irony that prevents Vallotton from ever quite settling, as a painter, into one signature style. He ranges restlessly from these paintings-as-design, through the more impressionistic naturalism of the interiors with Gabrielle, to the meticulous near-archaic realism of the self-portraits and the still lifes, the fleshy literalism of his nudes.

In 1898, not long before his marriage, Vallotton embarked on two series of scenes from the secret sexual lives of the bourgeoisie: first a sequence of 11 woodcuts, the Intimacies, then a series of paintings of similar subjects. Men and women are attracted, they desire each other, they make assignations, they can’t help it; they fight, they feel betrayed, they hate each other. It’s the eternal comedy of the sex war: banal, intoxicating. We don’t quite see them in bed together, but the bed and its suggestions, corners of white pillows poking up, is hinted at everywhere – or the sofa will do. These woodcuts were popular: their sheer ingeniousness, compressing dense narration into a small space, somehow miniaturising and making safe what is violent or sad in the subjects, and their strong whiff of misogyny. The woodcuts make the sex war amusing, seductive, wicked; the paintings are more troubling, and not everybody liked them.

The Red Room (La Chambre rouge), 1898

Intimacies V: Money (Intimités V: L'Argent), 1898

Intimacies VII: Five O'Clock (Les Intimités VII: Cinq heures), 1898

Intimacies I: The Lie (Les Intimités I: Le Mensonge), 1897

But I’m drawn deeply into these paintings, their painful unfinished stories, particularly The Red Room (1898), which is less stylised than others in the series. It’s worked in careful detail and the perspective is steady, although nothing is quite as naturalistic as in the interiors with Gabrielle – the couple’s faces and posture are conveyed in a few suggestive woodcut-like lines. The room isn’t at all like the patterned, papered, draped interiors Vallotton will paint when he’s married; this furniture is blocky, modern, low-slung, upholstered in plain brick-reds and hot oranges. Everything that feels feminine in the spaces Gabrielle commands is masculine here: most of the fussy bits and pieces belong to the woman who’s visiting – her gloves and a parasol and handkerchief left on the table-top. Even the man’s books are shut away in a glass-fronted bookcase: he isn’t thinking about reading now. There’s daylight: no doubt it’s the five o’clock that seems to have been the joke-hour for adulteries (it’s the title of one of the woodcuts).

Two concentrated passages of painting, in the middle and on the left, exact our attention – balancing them on the right is a suggestive tall oil lamp with a shade like frothy underwear. At the centre, above a closed hearth, there’s an oddly busy mantelpiece, ornamented with candles, flowers, and a mirror whose screening curtains – to screen off what, when, for whom? – are drawn back. A male bust, made in some black material, is broodingly intellectual yet somehow null, with its shiny high forehead – it’s based, apparently, on an actual portrait bust of Vallotton, as if he mocks his own artist’s detachment from the scene, voyeur looking the wrong way. The mirror, meanwhile, reflects a painting on the opposite wall, a tense family grouping by Vuillard, who had given the painting to Vallotton. It isn’t quite clear that it’s a painting; anyone not in the know might puzzle over these figures apparently reflected in a room where something so private is unfolding. The messy complexity of the mantelpiece, art muddled with life, seems to denote everything in the world that’s opaque, intricate, distracting.

What happens in the darkened doorway beside the mirror is so much simpler than all this, eloquent in fact in its simplicity, drawn in a few clean lines. A man and a woman hesitate in a doorway, which leads presumably through into the bedroom, although we can’t see anything beyond them but darkness (the curtains in there must be pulled across). They’re touching but not embracing, inclining together yet holding themselves back. He seems to coax her, and perhaps his leg thrust forward cuts her off from returning into the daylit room. She seems to balk at going on into the darkness, she’s sunk into herself, looking down, away from his importuning; yet even as she holds him off she also invites him, through her touch and the slope of her body towards him. We see his perplexity, a line in his forehead. Nobody’s violent, yet they’re troubled. In this moment of stasis they’re poised on the threshold between the two rooms, two states of being (politely apart, or nakedly together). As they stand hesitating, they’re intensely two separate selves; but they’re also lustful. The slants of their bodies rhyme together, we feel the potent connective tissue of their touches and glances. What’s happening is cheap and ordinary and eternal, it isn’t romantic: Vallotton paints it with a kind of fatalism. It’s simple: but it isn’t interpretable, not in any moralising schema. It is what it is. A man and a woman, bereft of their usual performances as their ordinary selves – guarded behind books and parasol – take a great risk, and Vallotton catches them in their act, so vividly intent, so animal and alive.

Tessa Hadley is a novelist and short story writer. Her most recent book is the novel Late in the Day (Jonathan Cape).

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet is at the Royal Academy of Arts from 30 June — 29 September 2019. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with Fondation Félix Vallotton, Lausanne.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?