Cristina Iglesias: the artist who transforms public space

By Debika Ray

Published on 16 November 2020

Cristina Iglesias, whose sculptures bring out the otherworldliness of the cobbles, stones, bricks and mortar of cities, speaks to Debika Ray about winning the 2020 RA Architecture Prize.

Debika Ray is a writer and editor.

When I speak on the phone to Cristina Iglesias in late March 2020, the world is undergoing the most rapid and radical overhaul of our collective notion of public space in memory, as people, from Hong Kong to California, sequester themselves indoors to avoid human contact for the common good. In London, where I am, the threat of coronavirus has led to a renewed appreciation for parks as an arena where we can enjoy a daily dose of the outdoors at a safe distance from others. Iglesias is in Torrelodones on the outskirts of Madrid – a city renowned for its public squares and nightlife that spills out onto the streets into the early hours – where people have been almost entirely confined to their homes since mid-March.

It’s a moment of reflection for us all, but not least for an artist whose work deals so directly with the public realm that so many of us now desperately miss. “Maybe I’m naive, but I honestly believe this experience is going to change us,” she says. In Spain, as elsewhere, she observes, virtual spaces for meeting and gathering have become more important than ever, as people seek to stay in touch with their loved ones and colleagues. “I think precisely because of that, after this we will better appreciate being close to others and being able to look at something real. Feeling close to a community is a necessary part of feeling alive and this will be so important when we come out of these terrible times.”

The Spanish artist was recently awarded the 2020 Royal Academy Architecture Prize, given to an individual or practice “whose work inspires and instructs the discussion, collection or production of architecture in the broadest sense”. Architect Norman Foster RA, chair of this year’s jury, said: “Successive generations of urbanists and artists have enhanced open civic spaces with public art in the form of statuary and fountains,” adding that the prize “pays homage to that enduring and vital tradition in its choice of Cristina Iglesias.” Foster has worked with Iglesias on projects including Forgotten Streams (2017, pictured above), an installation comprising three pools of water placed around his Stirling Prize-winning Bloomberg headquarters in London. The work brings a sense of enchantment and the organic to the hyper-efficiency of the modern urban realm through cast bronze formations that resemble dense, entangled foliage.

Previous winners of the RA prize have been architects: Japan’s Itsuko Hasegawa in 2018 and, last year, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, founders of US-based practice Diller Scofidio + Renfro. This year’s choice of an artist, who works around and within the spaces that architects create, is a novel one. It is also timely, since public art allows the citizen to activate the urban realm – and a poignant reminder, in the era of social distancing, that it is life and human interaction that transform cobbles, stones, bricks and mortar into the idea of a city, a concept built around cooperation, compromise and collective purpose.

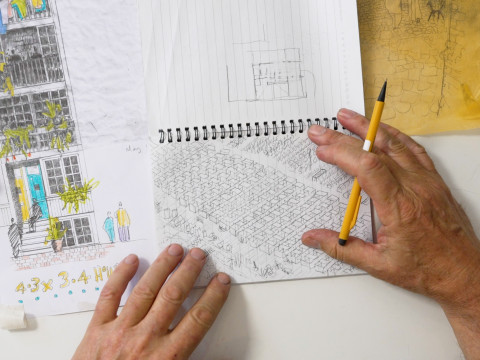

These collaborative values are inherent in the work of Iglesias – an urge partly driven by her unorthodox route to becoming an artist. Born in San Sebastián, she started a degree in chemical sciences at the city’s Universidad del País Vasco in 1976, before studying ceramics and drawing in Barcelona. In 1980, she took up a place to study sculpture at Chelsea College of Arts in London. This mix of disciplines and the experimental approach that these experiences encouraged laid the foundations for her career. “Drawing and working with clay was always, and still is, a way of thinking, but I was also very interested in science, particularly the laboratory part of it, the exploration,” she says.

Iglesias describes her time in London as formative, recalling an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1980, Pier and Ocean: Construction in the Art of the Seventies, that featured artists such as Donald Judd and Robert Smithson, who explored notions of space and construction. “I believe that it is in the poetic area of space where architecture and art relate,” she explains. Further inspirations include Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza and Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 pavilion in Barcelona, as well as specific typologies and forms, such as corridors, passages and mazes. However, she is less interested in architecture itself than in the voids it creates, which act as a platform for her work. “I like the spaces between buildings – the alleys, plazas and squares – as well as entrances, such as the lobbies and walls.”

I believe that it is in the poetic area of space where architecture and art relate. I like the spaces between buildings – the alleys, plazas and squares – as well as entrances, such as the lobbies and walls.

Cristina Iglesias, winner of the 2020 RA Architecture Prize

Since her studies in London, Iglesias has represented Spain at the Venice Art Biennale in 1986 and 1993 – as well as participating in the Architecture Biennale in 2012. She has also exhibited in the Guggenheim in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. Her collaborations with architects include Desde lo Subterráneo (2017, pictured below), five stone and iron sculptures containing pools of water that draw the eye deep into the centre of the earth, at Italian architect Renzo Piano Hon RA’s Centro Botín in Santander; and Doorway-Passageway (2006-07), which forms a towering sculptural entrance to Spanish architect Rafael Moneo’s extension to the Prado, evoking a sense of walking through a dense forest.

Her first collaboration with an architect was in 1987, with Belgian practice Robbrecht and Daem, on a sculpture at De Appel contemporary arts centre in Amsterdam, which led to further projects with them: a series of alabaster-and-glass cupolas in the ceiling of their office in Antwerp in 2000, and Deep Fountain (2001-06), a pool on the city’s Leopold De Wael Square, with natural formations rendered in cement visible when you stare into its depths.

The practice’s co-founder Paul Robbrecht discovered Iglesias’s work in the mid-1980s. “It caught my interest because there’s a deep consciousness in her work about architectural space: in the connection between the wall, floor, ceiling and corners,” he says. “And her work has a material impact. The textures, her treatment of light – these have a particular position towards the architectural whole.” It was not just the physical qualities of her work that attracted him, but also the emotional and philosophical ones. “There are memories that load the architectural context and give it universal meaning and transcendence,” he suggests.

It is these three qualities – space and context, texture and materiality, and memory and meaning – that Iglesias believes are intrinsic to her work. Ultimately, they are tools to draw people in – her artworks are not designed to stand aloof from people and their surroundings. “The act of going, of wanting to go and walk towards something, of passing something in the city – that is part of the piece, as well as the experience of being in it, around it, by it,” she explains. In the public realm, any intervention is always open to being used and interpreted as visitors want, which gives me room to play with illusion and perception and involve passers-by in a different way.”

The spatial qualities of her works create these illusions. For example, in many of her deep, well-like installations, the water disappears and appears in a way that draws you to look downwards. “The underground is a forgotten space that is full of metaphors about life and what lies beneath what we construct,” she continues. “Being made to look downwards also forces you to look more slowly, which I believe can move us and lead us to become introspective. For example, looking into a well you might feel vertigo but also a sense of being protected.” Tres Aguas (2014), installed in Toledo at three locations – a public square, a convent and a water tower (pictured below) – evokes introspection through moving waters. The work references the way in which Muslim, Jewish and Christian communities have lived alongside each other for centuries and shared the waters of the River Tagus for hygienic, symbolic and ritualistic purposes.

The texture and materiality of her works, which evoke a sense of nature more than architecture, seem to draw on Iglesias’s training as a maker and her experience of sculpting with clay.

When it comes to public art, there is always the danger that artistic questions are superseded by practical ones – safety, security and logistics. Ensuring her works stand alone and apart from these concerns, connecting emotionally and embodying her values and not just the prosaic demands of a private developer, is vital to Iglesias. “The work has to be its own independent entity – even if it’s in dialogue with the building, the plaza or a wall in the city,” she says. One example is Forgotten Streams at the Bloomberg headquarters in London: the work clearly acts as a security device – a sort-of moat around a high-profile, thus high-risk, corporate building. For Iglesias, however, it was a chance to create a gathering point in the heart of the city. “It transforms a private place into a public one, which is something that should be done more often.”

She does this partly through the organic, experiential nature of her works, which often stands in sharp contrast to the buildings they augment. Yet, as architectural historian and theorist Beatriz Colomina has pointed out, “they do not appear to be interventions” but “as if the ultra-technological and geometrically abstract modernity of the buildings contains within it a deeper, damp, organic layer that Iglesias uncovers and reveals”. The texture and materiality of her works, which evoke a sense of nature more than architecture, seem to draw on Iglesias’s training as a maker and her experience of sculpting with clay. Such qualities also, arguably, lend themselves well to public installations – one rarely touches artworks in a gallery context, but in a city it’s unavoidable. “Touch can trigger so many things in your imagination,” she says. “I even love the fact that you have to allow for a certain dirtiness with public sculptures – organisms or the grease of the hand transforms the work and becomes part of it.” Indeed, as with architecture,”the people are the inhabitants of the artwork”.

From the Summer 2020 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. The RA Architecture Prize is supported by the Dorfman Foundation (Founding Partner), Derwent London (Headline Sponsor) and the British Council (International Partner)

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?